Publication Details

| OLOR Series: | OLOR Effective Practices |

| Author(s): | Ruth Li |

| Original Publication Date: | 15 June 2018 |

| Permalink: |

<gsole.org/olor/ep/2018.06.15> |

Abstract

The activity explained below presents an innovative approach to the design and integration of collaborative writing projects using the Google Apps for Education online platform (OWI 4). The setting is a traditional, face-to-face high school English classroom in which students write in class simultaneously, each on separate devices, on shared Google Docs. In particular, I offer specific strategies for teaching students to write collaboratively in a variety of creative genres, including plays, poems, narrative essays, and speeches. While I taught the lessons in high school English classes, the strategies can be adapted for college composition, especially first-year writing courses. As illustrated in students’ writing samples, this approach can support students’ writing practices as students craft works that are cohesive in substance, structure, and style. In addition, integrating collaborative computer-mediated composition can encourage creativity, foster inquiry, and build a shared sense of community in the classroom as the digital dimension transforms the composing process (in accordance with OWI 11).Resource Overview

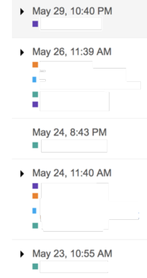

Resource Contents

1. Overview

[1] The activity explained below presents an innovative approach to the design and integration of collaborative writing projects using the Google Apps for Education online platform (OWI 4). The setting is a traditional, face-to-face high school English classroom in which students write in class simultaneously, each on separate devices, on shared Google Docs. In particular, I offer specific strategies for teaching students to write collaboratively in a variety of creative genres, including plays, poems, narrative essays, and speeches. While I taught the lessons in high school English classes, the strategies can be adapted for college composition, especially first-year writing courses. As illustrated in students’ writing samples, this approach can support students’ writing practices as students craft works that are cohesive in substance, structure, and style. In addition, integrating collaborative computer-mediated composition can encourage creativity, foster inquiry, and build a shared sense of community in the classroom as the digital dimension transforms the composing process (in accordance with OWI 11).

[2] In scaffolding the activity, I introduce the prompt, guidelines, and formatting; and share samples of published work in the genre, including screenplays, poems, book chapters, and speeches. Considering the traditional, face-to-face nature of the class, I then offer students time over the course of several days to form groups, generate ideas, draft, edit, and revise the project in class; then rehearse and perform the finished product for the class. Following the performances, I ask students to assess their own and their peers’ contributions and to reflect upon the process. Throughout the process, I actively monitor progress, encourage equal participation, and offer feedback to students. In essence, collaborative composing in a synchronous space enables students to reconceptualize writing as a continual, creative process of agency and communication.

Contextual Details

A. Type of institution: public charter high school (can also be applied to first-year college writing contexts)

B. Course level(s) and title(s): English 9-11, Creative Writing

C. Course type(s) (asynchronous, synchronous, online, hybrid): traditional, face-to-face instruction

D. Delivery platform(s): Google Docs within Google Apps for Education

1.1. Challenges of Collaborative Writing Activities

[3] Collaborative writing activities can be challenging to conduct in both analog and digital spaces, and in synchronous and asynchronous environments; for instance, using traditional pencil-and-paper methods, taking turns to contribute to a group writing project on paper or the board, can lead to inefficient processes or unequal participation. These challenges arise in digital spaces as well, as students do not always contribute equally to a task, though one benefit of Google Docs is that each student has equal access to the Doc and is able to write simultaneously. Another benefit, as explained below, is that teachers and students are able to view students’ written contributions to the projects, including which students contributed which sections, and to redirect students’ participation.

1.2. Affordances of Synchronous Collaborative Writing on Google Docs

[4] The synchronous environment of Google Docs offers several affordances: writing on a shared Doc enables multiple contributors to simultaneously provide and receive in-the-moment feedback, which improves efficiency and engagement and invites increased interactions. Consequently, the “meeting of minds” transforms the traditional processes of idea generation, drafting, revision, and peer review. The digital writing process empowers creative collaboration and fosters classroom community as students interact with each other face-to-face and on the screen throughout the drafting process.

[5] To establish roles for each student, I ask each group member to choose one character or part to write. In groups in which some more extroverted students tend to dominate the drafting and narrating, establishing character roles helps to balance the contributions. As the activity unfolds, students simultaneously engage in writing and narrating-about-writing, offering ideas to their peers, and monitoring or reflecting upon their own and others’ progress. In addition, students sometimes use the chat function on Google Docs to metacognitively discuss the draft-in-progress, so that online chat complements or supplements speaking aloud to each other.

[6] Moreover, students learn from each other through seeing and engaging others’ writing abilities while constructing a piece. As can be seen in the screenshots of the revision histories below, students who contribute less to their own lines sometimes take on roles beyond their own, as students edit each other’s words and sentences. In this way, students leverage the affordances of Google Docs for serving alternately as writers and editors, and as brainstormers and planners whose contributions are not always visible on the screen. Interactions with peers influence students’ writing practices as groups interweave idiosyncratic identities into a collective consciousness. While composing critically and creatively, students construct cycles of continuous connection, collaboration, and community.

2. The Teacher’s Role: Facilitating the Process

2.1. Viewing Google Docs Revision Histories

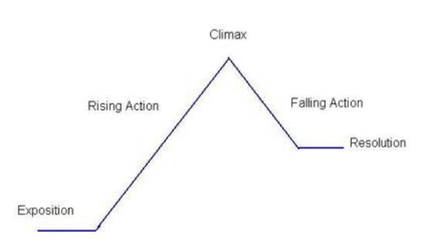

[7] While logged on to Google Docs on my laptop, I am able to access the Docs students share with me during the drafting process. As can be seen in the screenshot below, by clicking on “All changes saved in Drive” or “Last edit was made by ____________,” teachers can view a Google Doc’s revision history.

[8] The revision history screenshot below shows the times of each student’s contributions color-coded according to the student’s name. For example, on May 26 at 11:39 am, four students simultaneously edited the Doc.

[9] By clicking on a specific date and time in a Google Doc’s revision history, teachers can view the edits made to previous versions of the Doc retroactively at any point in the drafting process. As can be seen in the revision histories of sample student writing projects below, in order to identify and redirect cases of uneven or unbalanced participation, I am able to assess the quantity and quality of individuals’ contributions by checking the revision histories, which have shown various styles of collaboration, including the division of roles by lines, sections, paragraphs, and characters, depending on the genre of the writing project.

2.2. Viewing Live Edits on Google Docs

[10] To view multiple groups’ Google Docs, I toggle between multiple windows or tabs on my laptop while logged on to my Google account. Even as students offer instantaneous feedback to other as peer review becomes embedded in the drafting stage, I view the live edits as they occur on the screen; continuously monitor progress; provide guidance to individuals, groups, and the whole class using the suggestions mode; and plan and adapt instruction in the moment.

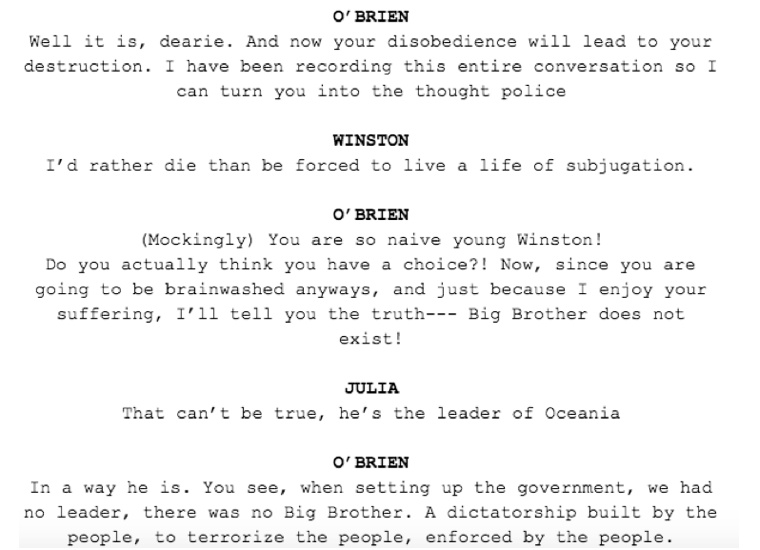

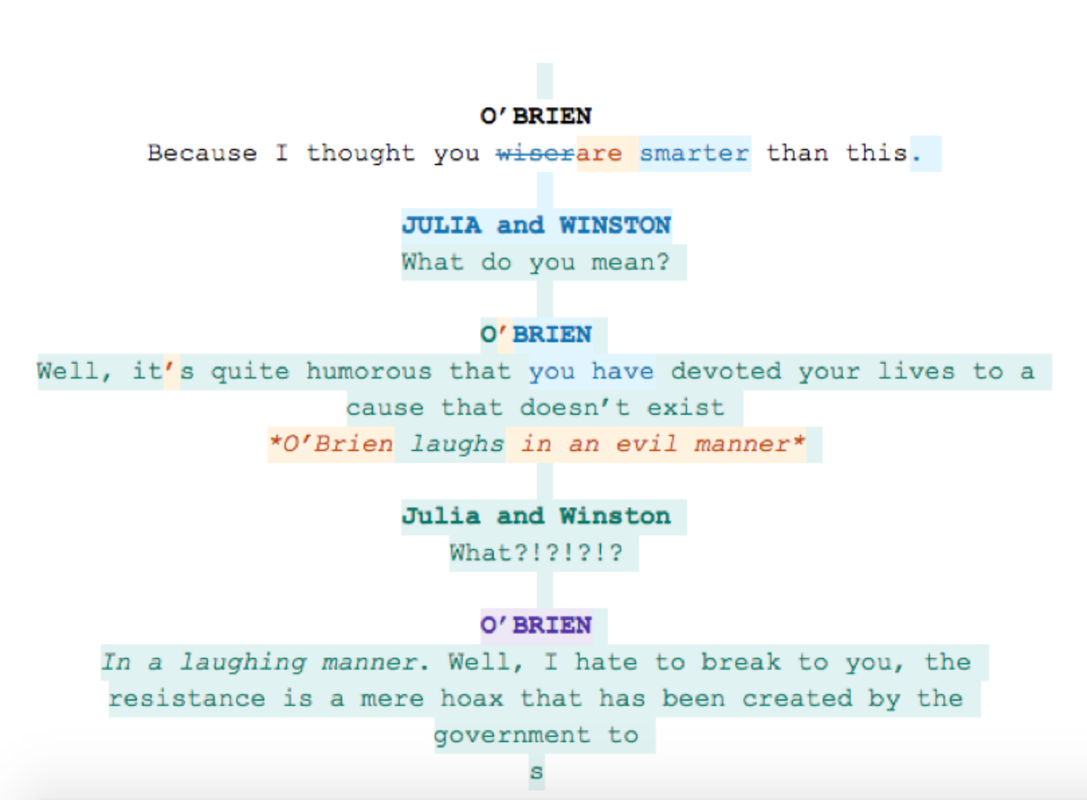

[11] As a caveat, however, I am careful not to become a domineering presence of surveillance, but to serve as a facilitator in the interest of encouraging independent student-centered learning (Effective Practice 4.5). To balance monitoring and distributing roles while offering students flexibility with the writing process, I establish clear expectations for equal contributions at the beginning of the activity, then take a step back to observe the face-to-face interactions and live edits as students begin to draft. By overseeing the writing process, I offer students freedom within the guidelines and only step in to comment on a Doc or speak with students individually when I notice unequal participation or inefficient processes. Depending on the mode of interaction, teachers can serve the roles of instructors, collaborators, consultants, editors, or viewers. In this sense, not only the writing and collaboration process, but also the feedback loop, can occur synchronously within and among the networks.

3. Literature

[12] The collaborative composition process expands in the digital dimension as online communication platforms such as Google Docs enable students to inhabit a single space simultaneously. Several studies have examined Google Docs as an effective platform for collaborative writing and have found that students generally hold positive perceptions of Web 2.0 writing (Brodahl, Hadjerrouit, & Hansen, 2011). In regard to the affordances of the platform in improving students’ writing abilities, Zhou et al. (2012) found that a majority of college students found the platform to be useful as its incorporation “made collaboration much easier,” “was simple to use,” and “encouraged editing and sharing among peers.”

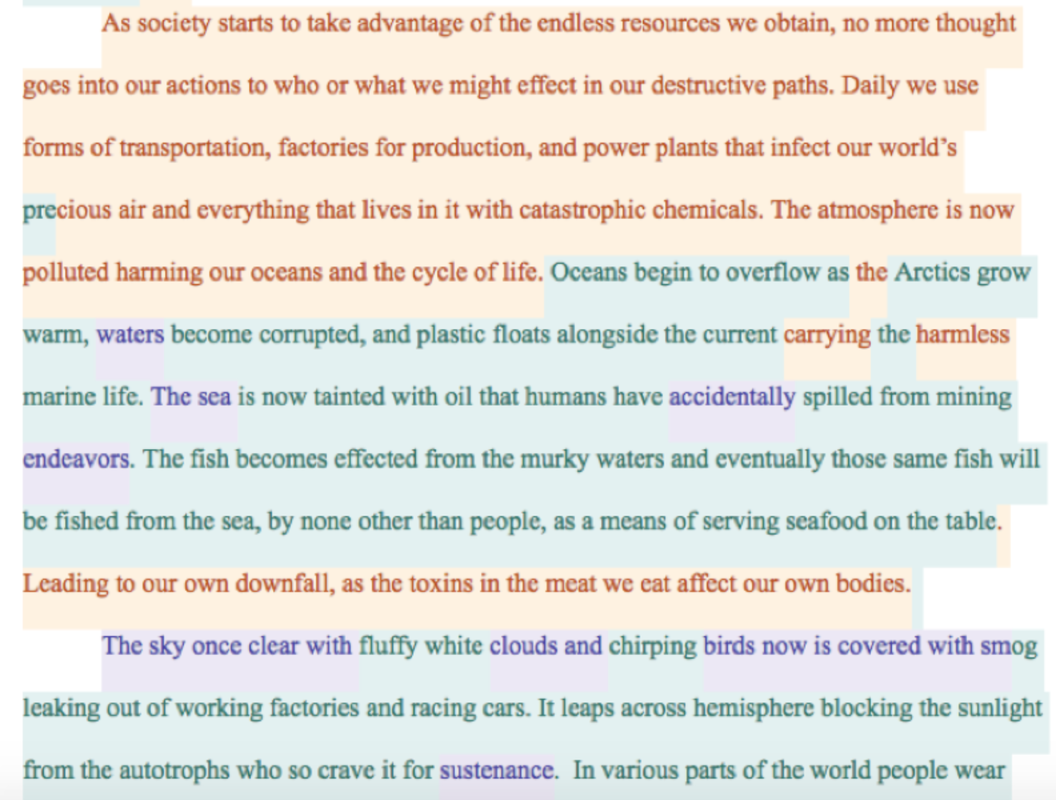

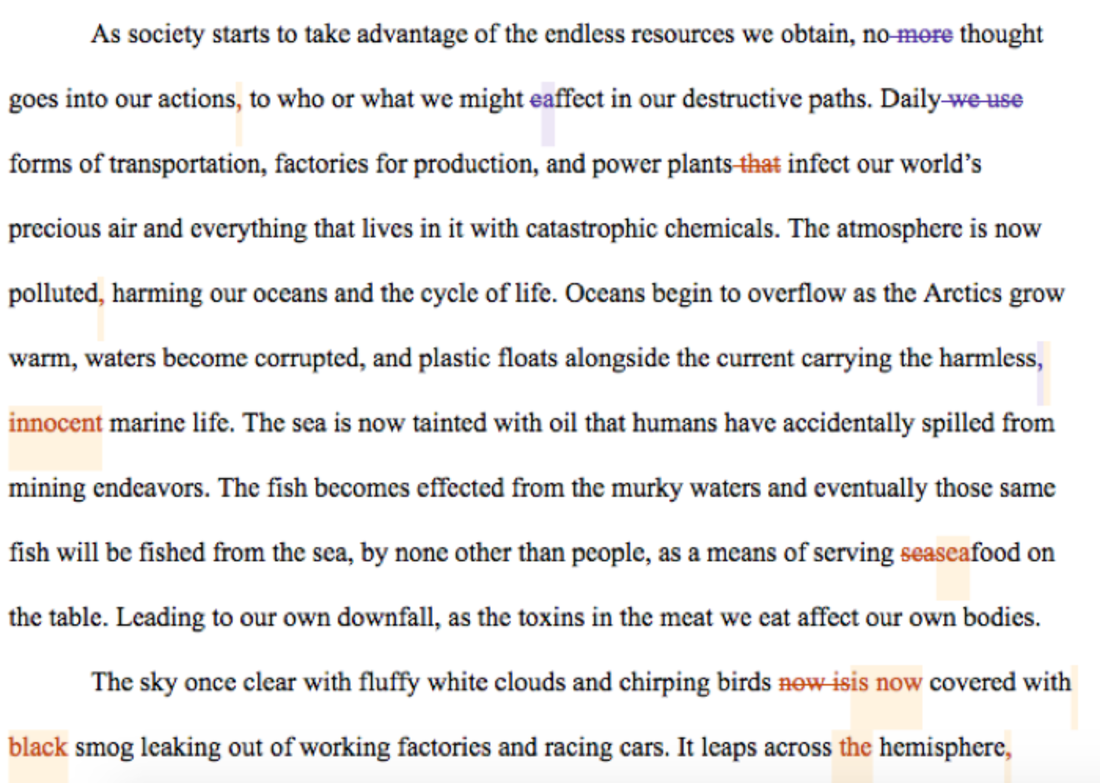

[13] Significantly, Suwantarathip and Wichadee (2014) concluded that groups of college students who integrated Google Docs in a collaborative writing assignment earned higher mean scores than those in face-to-face comparison groups; as the authors illustrate, the platform offered affordances in enabling students to read, edit, and provide and receive feedback on the constructions of words and sentences, such that the collaborative revision processes improved students’ grammatical abilities. Additionally, second language learners were found to “focus more on meaning than form” while writing collaboratively, and to make grammatical edits that generally increased accuracy (Kessler, Bikowski, & Boggs, 2012). Consequently, synchronous interactions with peers using Google Docs have been shown to improve students’ writing in relation to both content and format.

[14] Furthermore, while online platforms enhance literacy learning and writing instruction, scholarship has recognized the affordances of digital interaction in enabling original methods for supporting the stages of the writing process beyond content- and language-based revisions, including instructor feedback, peer review, and reflection. In particular, Woodard and Babcock (2014) describe a pedagogical strategy that fosters exchanges of feedback among peers, such as the annotation of classmates’ works-in-progress. The findings illustrate that peers offer each other comments for various purposes, including feedback that “encourages” revisions by the writer, or feedback that “affirms,” “debates” the techniques of, or “talks about” the writer. Therefore, not only are students able to directly edit each other’s writing, but also contribute meta-commentaries and annotations in order to offer others constructive feedback and reflect upon their own writing.

4. Implementation: Scaffolding the Collaborative Writing and Performance Process

- Introduce: review the prompt, guidelines, and formatting.

- Discuss: interpret samples of work in the genre.

- Write: brainstorm, draft, edit, and revise in groups in a shared Google Doc.

- Rehearse: divide and practice the roles/parts, lines, and staging.

- Perform: present the product to the class.

- Reflect/Review: assess each group member’s contribution to the task.

[15] While the sample assignment guidelines and step-by-step instructions below are relevant to playwriting, the activity can be tailored to other genres, including poetry and narrative writing.

4.1. Stage One: Introduction

[16] In introducing each collaborative writing activity, I begin by sharing the prompt and content and formatting guidelines for the relevant creative genre, which include, as described below, original playwriting and rewritten scripts of existing texts, poetry writing, and narrative and speech writing.

4.2. Stage Two: Review of Samples

[17] Additionally, in order to support students in generating ideas, learning genre conventions, and engaging in the writing process, I offer tips for story development and share models of pieces composed in each genre, including published and student-produced work. In essence, the sharing serves as a close reading activity, as students begin to critique media representations of popular culture, and to interpret the language writers express in poetry or the rhetorical strategies authors employ in historical speeches and narratives.

4.3. Stage Three: Writing - Structuring the Collaborative Composition Process on Google Docs

[18] After reviewing the prompt, providing guidelines for content and format, and sharing models of possible products, I let students choose groups during class in a face-to-face setting and begin to brainstorm topics and complete a prewriting worksheet (included below).

[19] The schools where I have taught offer students and teachers access to network-connected laptops, so students work from separate devices on a shared Google Doc while discussing collaboratively. Teachers in the schools often incorporate Google Apps for Education, so students are familiar with using the platform for completing assignments for their other classes, such as essays written in Google Docs and presentations created in Google Slides.

[20] The steps of the writing process are described below:

- Students choose small groups of three to four people and sit with their groups (each student has access to a laptop to collaborate on).

- One student in each group takes the initiative to create and share their group’s prewriting worksheet Google Doc (copied from the template below) with me and their group members.

- Students in each group collaborate on the prewriting worksheet on the shared Google Doc, contributing to the Doc simultaneously while working from separate devices.

- One student in each group takes the initiative to create and share their group’s play script Google Doc with me and their group members.

- Students in each group collaborate on the play script on the shared Google Doc, contributing to the Doc simultaneously while working from separate devices.

[21] I provide the following instructions on each class day, typically offering one week for students to write collaboratively in class. Significantly, I remind the class that each individual group member is responsible for contributing equally to the writing process.

[22] Sample Daily Directions:

Choose small groups of three-four people and sit with your groups (bring your laptops with you). Collaborate on a Google Doc to write the group play:

- One group member creates and shares the group's prewriting Google Doc with me and each group member.

- One group member creates and shares the group's play script Google Doc with me and each group member.

- Collaborate with your group to complete the prewriting worksheet.

- Collaborate with your group to write at least one page of the script.

- Include the correct script format.

- Each group member should actively edit the shared Doc in order to receive full credit (I will check the Doc’s revision history).

The completed script should be 3-4 pages long.

[23] To scaffold the process, each group completes a prewriting worksheet, shown below, which outlines the ideas and structure of the play. While I ask students to work from a template for the prewriting worksheet as a way to offer structure, in order to balance freedom and guidance, I allow to students write their plays on blank Docs after I share sample script formats and offer criteria including clarity, content, and conventions.

[24] Sample Daily Prewriting Worksheet:

Play Prewriting

Directions: Collaborate with your group members on a Google Doc to complete this worksheet.

Play Title:

Structure:

Include a clear structure and a narrative arc:

Exposition:

Rising action:

Conflict/climax:

Resolution:

Theme:

Include the central theme, lesson, or moral of the play:

Characters:

Include the characters’ names and group members’ speaking roles:

[25] To scaffold students’ understanding of the narrative arc (including the exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution), I share the graph above, which offers a clear visual representation of each stage of the plot structure.

4.4. Stage Four: Rehearsal

[26] Following the Arts Literacy Performance Cycle, in facilitating the rehearsal process, I instruct students to practice their roles in preparation for the performance. One of the benefits of Google Docs is that revision can occur throughout the drafting process, so students are able to continue making changes during rehearsal. Groups disperse across the classroom space, dividing roles, rehearsing lines, practicing gestures, and acting out the scenes, then revising the scripts as necessary.

4.5. Stage Five: Performance

[27] As preparations conclude and performances commence, the front of the classroom transforms into a stage, theater, or platform. In the interstitial space between imagination and reality, students not only physically perform their written ideas, but also share creativity, engage in civic discourse, and envision their roles as active agents, collaborators, and producers in Web 2.0. In a multimodal fashion, students incorporate visual, au/oral, spatial, gestural, and kinesthetic domains: especially while performing plays, students frequently integrate props, visual backgrounds, and sound effects. Performance deepens the dimensions of discourse; in projecting the page into a physical presence, the presentations serve as a potent reminder that even as the virtual environment enhances collaboration, physical embodiment remains essential to communication.

4.6. Stage Six: Peer Review and Reflection

[28] In integrating peer review, I have taught students to assess and evaluate each group member’s contribution to the task on a scale from 1 to 10, with 10 being the highest level of participation. I then average the ratings combined with my own observations to determine the participation scores. To help make the peer review process authentic, teachers can ask students to review the Doc’s revision history as a way to gauge their peers’ written contributions as well as to consider their peers’ spoken contributions, considering that students may have a better sense than the teacher of their group members’ overall written and spoken participation.

[29] Beyond the edits and comments students make to a Google Doc throughout the process, this closing activity invites students to reflect metacognitively upon their own as well as peers’ presence, participation, and productivity. In addition, I remind the class that participation encompasses not only performance, but also active listening and respect to peers during one another’s performances. By practicing heightened awareness and paying close attention to other groups’ creative choices, students gain new insights into the possibilities of collaborative composition.

5.Sample Student Collaborative Writing Projects

5.1. Collaborative Playwriting

[30] By writing collaboratively on topics of their choice, students can reimagine alternatives to existing endings in the literary canon; for instance, in my students’ recreation of 1984, O’Brien tells Winston and Julia that the resistance against the government of Oceania does not exist, then in a twist at the end, the servant, Martin, reveals that he is in fact behind the cause to overthrow Big Brother. Interestingly, as shown in the figure below, students adapt their writing to imitate the dystopian political themes and direct, terse style of Orwell’s original dialogue. For instance, the first lines spoken by O’Brien include the alliterative phrase “your disobedience will lead to your destruction” followed by the statement “I have been recording this entire conversation so I can turn you into the thought police” to further develop the significations that the first sentence expresses.

[31] Furthermore, a student contributes the line “a dictatorship built by the people, to terrorize the people, enforced by the people,” one that emerges as a dark reversal of the parallelism in Lincoln’s famous phrase from the Gettysburg Address, which we had read earlier in the year: “a government of the people, by the people, for the people.” In addition, in O’Brien’s second set of lines, it is shown in the revision histories that three writers in the group co-construct the script by freely editing each other’s words and phrases within sentences. As students recast canonical narratives and familiar phrases into a dystopian context, collaborative composing in a shared, synchronous space can enable students to enrich each other’s writing with deeper layers of meaning.

5.2. Collaborative Poetry Writing

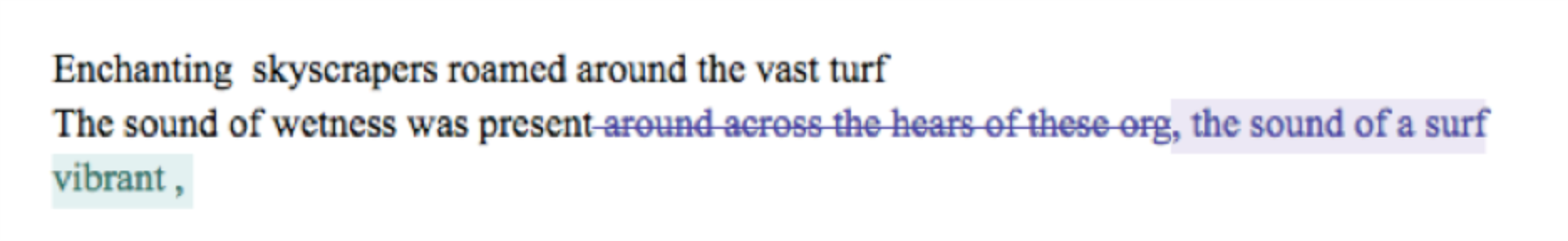

[32] Moreover, the influence of co-construction in interaction arises in poetry as well as prose. As illustrated in the beginning stages of a co-written poem shown below, a student shown in purple replaces a phrase with “the sound of a surf” to rhyme with the preceding line’s “turf,” and another shown in green adds the word “vibrant.” Interestingly, the synaesthesia of a “vibrant” “sound of a surf” echoes that of the “sound of wetness” present in the same line, in the literal echoing of the phrase and a mingling of the senses of sight, sound, and touch. In the spirit of magnetic poetry or word walls, the play of rearranging words and phrases, once an individual’s task, emerges as a shared, communal effort, a literal “meeting of minds” on a screen, then page. Thus, in the process of poetic creation, collaboration in a synchronous space likewise opens up a space for experimentation with evocative imagery, lyricism, rhyme, and rhythm.

5.3. Collaborative Narrative Writing

[33] Finally, in teaching the nonfiction narrative genre, I have assigned groups of students to re-envision the first chapter of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in the context of contemporary ecology and environmentalism. The paragraph presented in Figure 3 exposes the careful construction inherent in composition as students’ individual identities merge into a coherent voice. In examining the sample narrative, we can see the ways in which the descriptive language and somber tone of Carson’s chapter “A Fable for Tomorrow” has inspired the students’ writing; mirroring Carson’s rhetorical arc, the students’ paragraph begins with a broad sweep: “As society starts to take advantage of the endless resources we obtain…”

[34] Similarly, the construction of the sentence that begins the second paragraph, “The sky once clear with fluffy white clouds and chirping birds now is covered with smog leaking out of working factories and racing cars,” mirrors the original statement “The roadsides, once so attractive, were now lined with browned and withered vegetation as though swept by fire.” In these parallel statements, the students’ integration of our whole-class interpretations of the language contained in the chapter is apparent: the effect of the words “once” and “now” juxtapose the past and the present, yet the students’ version recasts the conditions in relation to contemporary environmental concerns of “factories” and “cars.”

[35] Significantly, students’ choices to expand upon each other’s work illustrates the effect of enabling co-constructive composition on a Google Doc: as seen in the first paragraph below, the writer labeled in orange extends the evidence presented by writer labeled in green with a concluding statement that relates the oil spills to human lives: “Leading to our own downfall, as the toxins in the meat we eat affect our own bodies.” In addition to structural development, students’ collaborative editing practices can sharpen one another’s writing in relation to style and word choice: in several instances, the writer shown in purple replaces words with others, including “endeavor” and “sustenance.”

[36] Yet even as individual elements of language are refined, the encompassing effect of a cohesive narrative is preserved: the substance and style merge into a coherent whole with a logical flow. Consequently, the sample illustrates that while students’ interactions and co-constructions with peers affect their writing processes on the micro-level of language use, collaborative writing simultaneously enhances global issues of meaning, tone, and structure.

[37] As illustrated in the screenshot, the interactions among writers are apparent: while the writer labeled in orange primarily composed the first half of the page, the student labeled in green drafted the latter half. Interestingly, the writer labeled in purple adds, refines, and revises words and phrases interspersed throughout the paragraphs, serving a role more akin to that of an editor than a drafter. In noticing the patterns of participation and division of duties, it is important for the teacher to consider the quantity and quality of the contributions when evaluating the process and finished product, including the various roles that students take on - as planners, writers, editors, and revisers.

[38] Over the lifespan of a Google Doc, the collaborative writing process mirrors the individual process as earlier edits expand the global content, while later changes tend to focus on local issues of language and form (as shown in Figure 8). In viewing the live revision histories, teachers and students can view a work-in-progress as its develops from process to product.

[39] As an additional example, Figure 3 below, a screenshot of one section within a group’s play based on 1984 captured at one moment in the drafting process, reveals a clear division of roles: the main writer of the section is shown in green, an editor of language and expression in orange, and secondary writers in blue and purple.

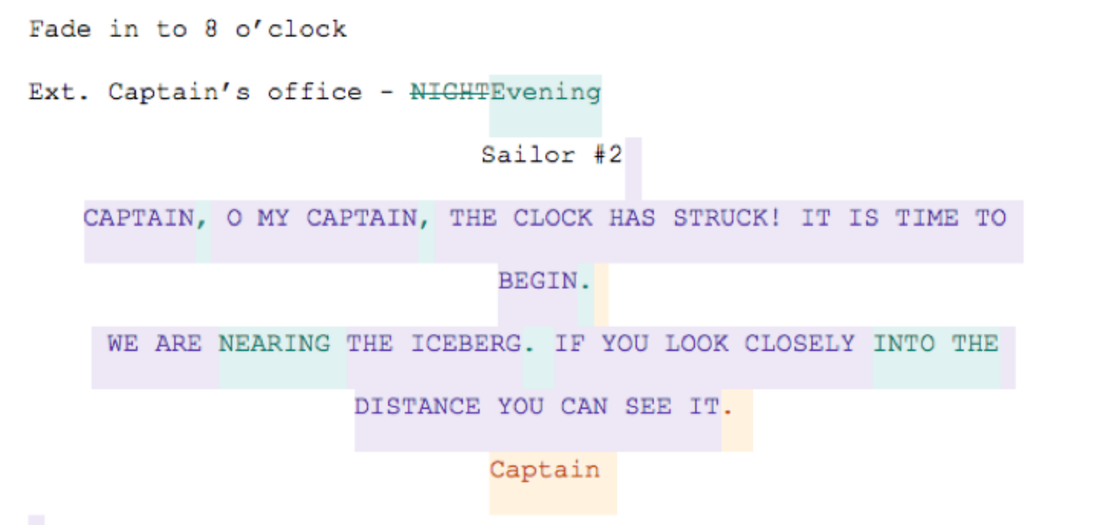

[40] In addition, Figure 4, a screenshot of a section from one group’s version of “How Titanic Should Have Ended” entitled “The Sinking of the Wealthy,” presents an interesting relationship between the writers labeled in blue and purple: the writer labeled in purple edits the writer in blue’s sentences by adding articles, prepositions, verbs, and punctuation as well as changing a word choice (from ‘night’ to ‘evening’).

6. Reflection and Limitations of the Approach

[41] Students’ interactions with peers throughout the collaborative composing process influence their writing practices on the micro-level in relation to patterns of word choice, as well as simultaneously enhancing the macro-level issues of meaning, tone, and structure. Significantly, writing with multiple collaborators in a shared, synchronous space demonstrates for students the continual, recursive drafting process, one that may be less apparent when an individual student composes linear, successive drafts using pencil and paper, then offers and receives feedback from peers and teachers during the later stages. Thus, in a sense, the peer review process is embedded within the structure of collaborative composition on a shared document, as edits as well as oral and written meta-commentary occur and recur throughout the lifespan of a Doc.

[42] Another skill that students gain in the collaborative writing process is cooperation or negotiation; as can be seen in the revision histories above, students often refine each other’s word choices and expand upon each other’s sentences. While it could be argued that editing others’ writing could be seen as intrusive or lead to conflicts between students, I have observed that students are open to others’ edits while negotiating roles and becoming aware of their own and others’ writing choices in the moment-by-moment process.

[43] There are limitations to the approach, as students did not always participate or contribute equally to the projects, and the quality and quantity of the writing varied according to the effort the students put in. In addition, while reviewing the revision histories of the collaborative poetry activity, I found several projects that were typed by only one student in the group. This might be another limitation to the activity: students may collaborative actively by sharing ideas orally with their group, but may not contribute equally to the writing on the Google Doc, which could lead to a lower evaluation from the teacher. In these cases, teachers can assess students’ contributions based on their observations as well as on the peer review evaluations.

[44] In addition, considering that perhaps the length and structural complexity of plays and narratives, as well as the division of characters’ roles in playwriting, lend themselves more to collaborative writing, it might be helpful for teachers to design group activities in genres that are conducive to collaboration. Overall, incorporating carefully structured scaffolds including the discussion of models of work in the genre; providing specific guidelines for content, organization, and formatting; as well as offering a space for rehearsal, performance, sharing, and peer review could encourage active participation and engagement among students in the class.

7. Required Resources

[45] In order to implement this activity, students and teachers should have access to the Google Apps for Education platform, particularly Google Docs, as well as network-connected laptops that enable synchronous access. Alternative applications could encompass other synchronous, collaborative platforms that invite real-time brainstorming, such as Evernote, Edmodo, Popplet, or RealtimeBoard. Common programs such as Microsoft Word could also be used, but the asynchronous nature might not afford the benefit of simultaneous writing and editing by multiple student

8. Acknowledgements

[46] I presented this activity at the Great Plains Alliance for Computers & Writing Conference in 2017 and the University of Michigan Graduate School of Education Conference in 2018, and I appreciate the feedback I received at both conferences. I am grateful for the comments from the OLOR editors and reviewers - Jason Snart, Heidi Harris, Michael Madson, and Beth Hewett - and from Anne Gere and Barry Fishman on an earlier version of this article.