Publication Details

| OLOR Series: | OLOR Effective Practices |

| Author(s): | Amy Cicchino, Lindsay Clark, and Traci Austin |

| Original Publication Date: | 25 July 2020 |

| Permalink: |

<gsole.org/olor/ep/2020.07.25> |

Abstract

Using screenshots from our own courses, we demonstrate how Ally brought specific accessibility issues to our attention. We also discuss how this experience prompted us to consider the degree to which these changes increase the accessibility of these resources and what other considerations might be overlooked by the program. This practice addresses OLI Principle 1: "Online literacy instruction should be universally accessible and inclusive."

Resource Overview

Resource Contents

1. Overview

While it is true that online courses can offer students and teachers flexibility in timing and location, online courses can also complicate accessible learning if course materials do not meet standards for web accessibility (Hong, Ivy, Gonzalez, & Ehrensberger, 2007; Lambert & Dryer, 2018; Goodman et al., 2018). Instructors must deliver accessible content and iteratively reflect on course design practices as accessibility is one of the essential components to effective online instruction. However, finding effective methods for teaching online faculty about accessible course design can be challenging. Traditional methods for faculty development (e.g., workshops, orientations, lunch and learns) are rarely feasible for professionalizing faculty who might be limited in their ability to attend in-person professional development events because of personal or environmental factors. For instance, the recent move to rushed remote instruction following COVID-19 left many instructors underprepared for accessible online instruction. Due to the pandemic, in-person workshops were not possible. The result of these limitations often lead to uneven accessibility practices across a program. In response to this need, this resource introduces instructors to Blackboard Ally, a technology that can help them learn about accessible course design, as well as identify barriers to accessibility in their instructional materials. It is important to note, adopting Blackboard Ally is not a panacea for accessible instruction--especially if some instructors are unwilling to modify their course materials. However, this tool offers instructors individualized feedback on the steps they can take to increase the accessibility of their course content. Program administrators can then leverage this feedback to foster continuing discussions about accessible practices across a program.

Contextual Details

A. Type of institution: Four-year regional university, though the practice can be used in all higher education institutions with access to accessibility checker tools, like Blackboard Ally

B. Course level(s) and title(s): upper-level business writing or business communication courses

C. Course type(s) (asynchronous, synchronous, online, hybrid): This practice can be, and has been, used in all course types—the focus of this piece uses Blackboard Ally within online and hybrid contexts

D. Delivery platform(s): Any learning management system, including Blackboard, Canvas, Moodle, D2L, and others

2. Tools and Platforms

In Summer 2019, a new tool intended to support accessible instructional practices was implemented at one of the authors’ universities. Blackboard Ally (Ally), released in 2017, is a tool designed to help instructors make course content in learning management systems (LMSs) more accessible. The benchmarks Ally uses to determine accessibility are drawn from common standards, such as Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1 (Blackboard, n.d.). WCAG 2.1 encompasses recommendations for making web content accessible to those with “blindness and low vision, deafness and hearing loss, limited movement, speech disabilities, photosensitivity, and combinations of these” along with “some accommodation for learning disabilities and cognitive limitations” (W3C Web Accessibility Initiative, para.1). Ally helps instructors learn about and address accessibility issues in two ways: first of all, it automatically reviews course materials and assigns a visual accessibility “score” to individual instructional items. Second, after a score is assigned, Ally offers practical guidance for modifying content to increase accessibility and raise the score.

At a broader level, Ally has a stated goal of “build[ing] for sustainable change in behavior” among instructors when it comes to understanding and addressing accessibility issues in learning materials. In the feedback and guidance function, Ally often includes links to resources for learning more about specific accessibility-related topics. For example, a common technique is to use color to highlight information on a document or on screen (e.g., putting due dates in red text on a syllabus or assignment sheet). Ally will highlight this text as having insufficient contrast, which may make it difficult for students with colorblindness to read. In the advice provided for fixing the text, Ally includes a recommendation to download the Paciello Group Color Contrast Analyzer so that instructors can learn how to address contrast issues in the future.

For students, Ally offers choices and flexibility for interacting with content in the LMS. For example, when an instructor posts a file, Ally will automatically create alternate forms of that file (e.g., audio, Semantic HTML, ePub, Electronic Braille, BeeLine reader, and translation) (Blackboard, 2018). This function allows students to choose the file format that is best for them with no additional labor for the instructor.

While Ally is a Blackboard product, it can be integrated into other learning management systems, such as Canvas, Moodle, and Brightspace (Blackboard, 2019). If an institution does not have Ally, other resources exist to help instructors design accessible content for their courses—these include:

- IBM’s Accessibility Checklist

- Personal, Accessible, Responsive, Strategic: Resources and Strategies for Online Writing Instructors (Borgman and McArdle, 2019)

- Universal Design Online content Inspection Tool, (UDoIt): https://training.it.ufl.edu/training/items/udoit.html

- WebAIM’s accessibility resources

While these resources cannot interface with an LMS, they still provide guidance on the design steps one can take to make course material more accessible for students. Below we discuss how Ally’s scoring and guidance functions illuminated common accessibility issues for us. We discuss how instructors can use accessibility trackers to avoid errors and better understand accessibility in learning materials.

3. Advantages of Praxis

As explained above, Ally is a useful tool for understanding the accessibility of online content. Still, designing perfectly accessible content can prove both complicated and challenging. Issues of accessibility can be layered and nuanced and can result in well-intentioned instructors missing the mark. According to a 5-year study by Ally, the average overall accessibility score for higher education institutions is 30.6%, suggesting that the majority of learning materials provided to students do not account for or accommodate students with varied accessibility needs. This research highlights many aspects of accessibility that concern organization and design, as well as our assumptions about what will work for students. Analyzing 21 million anonymized content items from 700,000 courses, their research revealed that overall accessibility has increased (27.5% to 30.06%). However, specific accessibility issues had worsened, such as poor contrast and heading issues (“Unpacking course content accessibility,” n.d.). In the following sections, we discuss how Ally revealed easily overlooked accessibility considerations and student needs.

Using screenshots from our own courses, we demonstrate how Ally brought specific accessibility issues to our attention. We also discuss how this experience prompted us to consider the degree to which these changes increase the accessibility of these resources and what other considerations might be overlooked by the program. It is important to note that Ally has limitations in terms of ensuring universally accessible resources for students and providing accessibility support for instructors. What Ally does offer, though, is awareness-raising engagement with issues of accessibility that may not be obvious and resources to help instructors develop an accessibility mindset.

4. Supporting Literature

Accessibility checkers, such as Ally, can help online literacy instructors create course materials that meet WCAG 2.1 standards—even if those instructors are unfamiliar with these guidelines and how to apply them. By evaluating materials within the LMS according to accessibility standards, accessibility checkers alert instructors to materials that are inaccessible for students using assistive technologies. Additionally, these checkers support instructors’ awareness of accessibility guidelines and can provide them with strategies for improving inaccessible content (Bastedo & Swenson, 2020). Specifically, accessibility checkers will identify missing alt-text, missing hierarchy and navigation markers, missing transcripts, missing character recognition in PDFs, and missing metadata—a full list of accessibility standards in Ally is available on their website. Ally, specifically, will also translate materials into other formats (e.g., Braille, audio, tagged PDFs, and html) automatically for students.

There are, however, limitations to automating the process of vetting materials for accessibility. First, Ally helps ensure course materials are ADA-compliant but will not identify other aspects of universal design that will make material more cognitively accessible for students. For example, Ally will inform an instructor that they need to add alt-text to an image, but it will not signal if their curriculum lacks low-stakes opportunities for students to apply their learning or monomodal presentations of content—two issues identified by universal design (Womack, 2017; CAST, 2018). Put differently, Ally evaluates content for a specific kind of accessibility--ADA-compliance--resulting in an incomplete view of accessible course design. Using Ally will improve the existing course content, but the technology alone cannot support larger conversations about accessible instruction across a program.

5. Implementing this Effective Practice

Each file uploaded into the LMS runs through Ally’s accessibility check which generates a “gas gauge” icon to represent the accessibility score and corresponding color gauge. A green gauge represents high accessibility (score between 99% and 67%), an orange range represents moderate accessibility (score of 66% to 34%), and a red gauge indicates low accessibility and scores from 33% to 0. To see how Ally functions, one author uploaded three documents to her LMS: two PDF handouts that were text-based and the third was a PDF containing an image (.jpg) of a grading rubric.

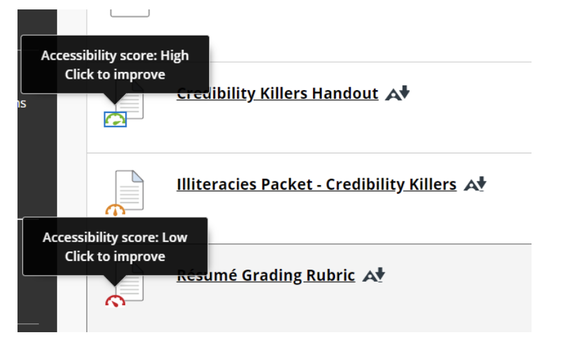

As seen below, these three files received all different colors and scores once scanned by Ally:

As shown in Figure 1 above, the Credibility Killers Handout was considered an accessible document, generating a green gauge; the Illiteracies Packet received an orange, or moderate accessibility score; and the Resume Grading Rubric received a low accessibility score, marked by a red gauge. Interestingly, all three documents were PDF files, so it was not clear initially what differences caused the variation in scores. All three were entirely text-based and believed to be free of any features that could have lessened the accessibility. However, as we explored the reports generated by Ally for these different resources, we began to realize what issues contributed to these scores.

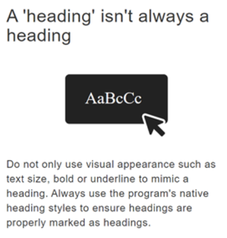

To view particular problems with these resources, Ally provides a “click to improve” function that initiates a pop-up window (shown in Figure 2) explaining the accessibility issues with the document and suggesting potential actions to improve accessibility. In this instance, Ally identified the lack of headings as the major issue in this document and provided a link to understand “what this means” and “how to add headings.” These additional links are extremely helpful information for instructors. The clickable box for “what this means” initiates another pop-up message that explains headings, shown below in Figure 3.

The message prompts the instructor to return to the original document and make specific edits that include adding headings using the word processing program’s style features, as well as removing features that affect the accessibility such as color and other visual design elements. In this example, we had signaled our headings visually by making them all blue but had not marked them as headings in Word's style formatting section. While most students would be able to see the heading, a student with color-blindness might not be able to differentiate the color's significance, and an assistive technology would not recognize the blue text as a heading in the document's navigation.

The Ally report on the rubric assigned a red gas gauge symbol and a score of 0%, with the major issue noted as “The PDF is scanned.” As mentioned above, this rubric document was actually an image—a screenshot taken on the LMS, pasted into a Word document, and converted to a PDF document. Rather than suggesting any immediate fixes, the pop-up encourages the instructor to return to the original source and use a different format. Essentially, instructors could “trick the system” at this moment. In this situation, for example, the instructor could go back to the original screenshot of the rubric, save it as an image, and assign a caption to it on the LMS. However, a more accessible fix would be for the instructor to save the rubric as text (not an image) so a screen reader could interpret the words in the rubric.

Similarly, the pop-up window for the document “Action verbs” is seen in Image 4, indicating the reasons Ally assigned a moderate accessibility score of 51%: images with missing descriptions and missing titles for document navigation. Clicking the “Fix” button allows the instructor to type a simple caption that is automatically added to the document. By applying this recommended change, according to Ally, the accessibility score would increase significantly, generating a green gauge. While the tool will identify and address issues like missing headings in documents or captions on images, Ally is not, of course, without limitations. For example, the PDF title fix was not yet available, as shown above.

Likewise, while Ally will create audio versions of files, it does not have the capability of reviewing an instructor’s original files for clarity, the presence of captions, or other factors that may impact accessibility for students with hearing challenges. Moreover, our experiences assessing generated Ally reports led us to consider the extent to which these changes or edits are universally accessible. Theoretically, a low score on a text document that is missing headings or utilizing poor contrast can be avoided by making the text document into an image (like a .jpg) and adding a caption. Perhaps, then, the onus is still on us to adopt a mindset that applies accessibility thinking to resources prior to their addition to the LMS.

6. Conclusion

Though not every institution has integrated Ally into their LMS, engagement with an accessibility checker tool of some kind supports an awareness of online accessibility in course material design. In all, Ally is a helpful tool in that it guides instructors to notice and correct issues of accessibility in their materials, especially with regards to common accessibility errors. In the table below, we address five common issues Ally identifies in addition to an accessible practice for that issue and an explanation of how that practice facilitates accessibility:

Table 1: Five Common Accessibility Issues

|

Ally’s identification of these accessibility issues serves as an important awareness-raising tool for online instructors. To get closer to the goal of accommodating as many student learning needs as possible, instructors must continue to monitor and refine the accessibility of learning resources and adapt them to changing student and educational needs. Whether teaching or training online, we must stay agile in the ways we can support students, staff, and faculty who work and learn in digital spaces, but Ally offers us a place to start.

The authors of this article certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

7. References

American Federation for the Blind. (n.d.). Screen reading technology and refreshable braille displays. https://www.afb.org/blindness-and-low-vision/using-technology/assistive-technology-videos/screen-reading-technology

Bastedo, K. & Swenson, N. (2020). General accessibility guidelines for online course content creation. In S. L. Gronseth & E. M. Dalton (Eds.) Universal Access through Inclusive Instructional Design: International Perspectives on UDL. Routledge, p. 208–217.

Bee Line Reader. (2017). Bee line reader. https://www.afb.org/blindness-and-low-vision/using-technology/assistive-technology-videos/screen-reading-technology

Blackboard, Inc. (n.d.). Blackboard Ally for LMS datasheet https://www.blackboard.com/ resources/blackboard-ally-lms-datasheet

Blackboard, Inc. (2018). Blackboard help: Ally: Alternative formats. https://help.blackboard.com/Ally/Ally_for_LMS/Student/Alternative_Formats

Blackboard, Inc. (2019). Blackboard Ally. https://www.blackboard.com/accessibility/blackboard-ally.html

Blackboard, Inc. (2019). Unpacking course content accessibility. https://www.blackboard.com/sites/default/files/2019- 09/One%20Pager%20Blackboard%20Ally%20%20Course%20Content%20Accessibility%20Data%20Study.pdf

Borgman, J. & McArdle. C. (2019). Personal, accessible, responsive, strategic: Resources and strategies for online writing instructors. WAC Clearinghouse.

CAST. (2018). Universal Design for learning guidelines version 2.2. http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Hong, B. S. S., Ivy, W. F., Gonzalez, H. R., & Ehrensberger, W. (2007). Preparing students for postsecondary education. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 40(1), 32–38.

IBM. (2019, June 3). IBM accessibility checklist. https://www.ibm.com/able/guidelines/ci162/accessibility_checklist.html

Goodman, J., Melkers, J. & Pallais, A. (2018). Can online delivery increase access to education? Journal of Labor Economics, 37(1), 1-34.

GSOLE. (2019). OLI principles. https://gsole.org/oliresources/oliprinciples

Lambert, D. C. & Dryer, R. (2018). Quality of life of higher education students with learning disability studying online. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 65(4), 393-407.

Paciello Group. (2020). Colour contrast analyser. https://developer.paciellogroup.com/resources/contrastanalyser/

University of Florida IT. (n.d.). UDOIT. https://training.it.ufl.edu/training/items/udoit.html

Web Accessibility Initiative’s World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). (2020). Web content accessibility guidelines (WCAG) overview. https://www.w3.org/WAI/standards-guidelines/wcag/

W3C Web Accessibility Initiative. (2018). Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1. https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG21/

Web AIM. (2019). Web accessibility for designers. https://webaim.org/resources/designers/

Womack, A. (2017). Teaching is accommodation: Universally designing composition classrooms and syllabi. College Composition and Communication, 68(3), 494-525.