Publication Details

| OLOR Series: | OLOR Effective Practices |

| Author(s): | Theresa Evans |

| Original Publication Date: | 10 March 2021 |

| Permalink: |

<gsole.org/olor/ep/2021.03.10> |

Abstract

Team projects are always difficult to supervise, but online courses present unique challenges: The instructor has limited opportunity for real-time observations of and interactions with student teams, as they collaborate virtually in digital spaces. Still, virtual collaboration is an important skillset to develop, given that distributed teams are becoming more common in the workplace. Team projects in online courses create—for both instructors and students—a double burden of working with subject content and developing successful strategies for virtual communication and work processes (Paretti et al., 2007, p. 331). I encourage a layered approach to teamwork through my efforts to scaffold—to structure—team projects in online writing courses. Students have ongoing scheduled check-ins with me, which they can use as a starting point for their more detailed team schedule. These check-ins include at least one synchronous meeting and a combination of individual and team assignments that build towards the final deliverables.Resource Overview

Resource Contents

1. Overview

[1] Team projects are always difficult to supervise, but online courses present unique challenges: The instructor has limited opportunity for real-time observations of and interactions with student teams, as they collaborate virtually in digital spaces.

[2] Still, virtual collaboration is an important skillset to develop, given that distributed teams are becoming more common in the workplace. A distributed team is defined as a group of individuals who work together virtually from disparate geographies and time zones. Some distributed teams collaborate virtually on a specific project and then disperse once that project is complete.

[3] Distributed teams may be more common now, but they are not new, and they are not unique to digital environments: In the early 1990s, I was the lead copywriter in the marketing services department of a telecommunications company that had regional divisions and sales offices scattered across North America. Our marketing services team regularly worked on promotions for specific sales offices, corporate or regional programs, and product lines. We worked with distributed teams assembled for a particular project, relying mostly on overnight delivery services, land-line phones, voice mail, and fax. We also began using voice-conferencing systems and early video-conferencing systems (large systems, which the company had begun selling and installing for businesses and institutions). The voice-conferencing system we used recorded conversations and stored them for two weeks. This feature was a great help to me and also illuminating in terms of how much information it is possible to miss, forget, or misunderstand from a real-time conversation. Over time, the tools of collaboration have changed, but the human process has remained consistent: Collaboration will always require relationship-building and a foundation of trust.

[4] Collaborative writing projects are accepted as a best practice. Wolfe (2010) noted that collaboration in the workplace is the norm, given that most projects require the expertise and perspectives of a range of individuals. On the other hand, teams in the workplace do fail, usually due to poor human interactions, and businesses are pressuring educators to teach collaborative skills (Wolfe, 2010). Paretti et al. (2007) emphasized that “including collaboration is not the same as teaching it, and collaboration in distributed environments involves more complex dynamics than collocated work” (p. 331). Team projects in online courses create—for both instructors and students—a double burden of working with subject content and developing successful strategies for virtual communication and work processes (Paretti et al., 2007, p. 331). On the other hand, expecting students to learn how to collaborate by doing is ineffective in any course delivery platform.

[5] Wolfe (2010) identified three methods of collaboration: face-to-face, divided, and layered:

- In face-to-face teamwork, students work together synchronously on most tasks, which can lead to negative power dynamics and limited participation from some team members (Wolfe, 2010, p. 8). Given the availability of videoconferencing platforms today, online students may attempt to use this method, especially those who believe teamwork happens only when all team members are working in the same “space” at the same time. These students may also have concerns about each team member putting in equal time on the project.

- In divided teamwork, the team members are assigned parts of the document and then the document is assembled at the end (Wolfe, 2010, p. 8). This method is often used by students who see collaboration as simply dividing up the end product, which, without regular communication, can lead to missing sections or sections that do not come together to form a coherent work.

- In layered teamwork, team members are assigned roles, but they are all responsible for and contribute to the developing document (Wolfe, 2010, p. 8). This method is most common in the workplace, especially given that team members are usually hired into specific roles within an organization. Student teams using this method are usually the most successful because they are not focused on logging equal time in meetings or contributing equal parts of the work. Instead, they are focused on a more equitable process of using the key strengths of individuals to achieve a common goal.

[6] I encourage a layered approach to teamwork through my efforts to scaffold—to structure—team projects in online writing courses. Wolfe (2010) recommends a “task schedule” (p. 10) that includes a mix of approaches, using the “most appropriate collaboration method for various stages of a project” (p. 10). Students have ongoing scheduled check-ins with me, which they can use as a starting point for their more detailed team schedule. These check-ins include at least one synchronous meeting and a combination of individual and team assignments that build towards the final deliverables. In Fall 2020, when all my face-to-face courses went online because of Covid-19, I avoided full-roster synchronous online class meetings in favor of weekly half-hour team videoconferences over the entire six weeks of the team project.

Contextual Details

A. Type of institution: Four-year research institution

B. Course level(s) and title(s):

- 200-Level Professional Communication for Business

- 300-Level Technical Writing

C. Course type(s) (asynchronous, synchronous, online, hybrid):

- Online: asynchronous with synchronous team conferences

- Hybrid: online and face-to-face

D. Delivery platform(s):

- Canvas

2. Structure Provides both Supervision and Support

[7] In the online course, student attendance and participation are measured primarily through successful and timely completion of assignments. As mentioned earlier, team projects complicate the ability to measure participation because instructors have few opportunities to observe team dynamics or to interact with teams. Hart-Davidson (2019) noted that, in a face-to-face classroom, he “can get a very reliable measure of how well everybody is doing, who is engaged and who is not, who might need my help with something, and who among the group is willing and able to help others” (p. 95).

[8] Although the face-to-face classroom does provide more immediate clues about student engagement, direct observation does not replace the need for instruction in team collaboration. Regular, scheduled check-ins can provide the kind of intentional interactions that also provide opportunities for ongoing instruction and supervision. For example, each team member submits regular individual assignments, such as a short list of annotated sources for the team project, followed by small drafts of writing that demonstrate the ability to synthesize those sources for the team document. Using smaller assignments to structure the larger project allows me to offer ongoing feedback, grant students the freedom they need to manage their own teams, and minimize the surveillance required to keep them on track to deliver projects on time.

[9] I do distinguish “supervision” from “surveillance.” For team projects, I define “supervision” as providing structure and guidance to keep students on track to successfully complete the assignment. I define “surveillance” as any method of project supervision that lacks transparency, reduces trust, or is punitive in nature. For example, I don’t ask teams to share their Google Doc with me, unless they are requesting immediate feedback or if they report a team member’s lack of contribution to the project.

[10] Surveillance mode is not the best option for supervising teams. Not only does it set a negative tone for the student/teacher relationship, but it also robs students of the opportunity to develop their ability to independently solve problems without the instructor—or the institution—looking over their shoulders. By scaffolding team projects with continual checkpoints, I provide opportunities for students to reveal their engagement—or lack of engagement—in the project.

3. Available Research Provides Strategies for Creating Structures

[11] Instructors can communicate immediately with students in a face-to-face class with a look or a gesture, but that becomes more difficult online, meaning not only students, but also instructors, need to learn strategies for virtual collaboration and avoid acting on implicit but unexamined assumptions about what collaboration means. Mehlenbacher et al. (2018) argued, “If we mean to encourage collaboration and the production of collaborative assignments, we must develop a clearer understanding of what we mean by collaboration, and more focused strategies on how to effectively develop organizational structures within collaborative environments” (p. 212).

[12] Structure is important, but too much of it can inhibit creativity and risk-taking. Mehlenbacher et al. (2018) cautioned about the use of collaborative platforms like Google Docs:

When an instructor decides to use software with a “revision history” feature, the instructor ought to think about the ways that feature functions as a type of surveillance tool. Not only does such a feature provide instructors with certain kinds of observational power and also evidence to support evaluation decisions but also this changes the dynamics among students and the kind of composing they will perform. (p. 215)

[13] A good policy then might be to allow students to decide when and if they will share their Google Docs with the instructor. Instructors always need to be conscious of whether their desire to support students by imposing order on team projects starts to lean too much towards surveillance and rigid authority (Mehlenbacher et al., 2018, p. 212). Still, students obviously will have less authority than the instructor to persuade teammates to communicate with them or to contribute to projects in a timely fashion. Sometimes a team will need extra support, especially when negotiating the challenges of a difficult, noncommunicative, or noncontributing team member.

[14] A simple misunderstanding can be cleared up easily; personality conflicts and unequal contributions to the project are more difficult to address. As most instructors know, differing levels of engagement and issues of control can lead to resentment among students who feel they are doing most of the team’s work or who feel they have no say in the team’s work. Further, one difficult team member can derail the team’s project, leaving all team members with a disappointing grade. Understanding the common causes of negative collaborative experiences is the first step towards encouraging more effective collaborative experiences.

4. Start with Collaborative Learning Outcomes

[15] Mehlenbacher et al. (2018, p. 213) outlined four key principles for using collaboration in the virtual classroom, based on four learning outcomes and general strategies to achieve them:

1. Collaborative Goal Setting

[16] Provide, prior to setting up groups, guidance on collaboration, including suggestions about team leadership, project scope definition, and tasks.

2. Collaborative Writing Process

[17] Give students a sense of the challenges specific to collaboration, such as issues related to team conflict, content generation, and overall stylistic and organizational consistency (provide them with examples to emulate and to avoid).

3. Collaborative Revision Process

[18] Frame comments and feedback as formative and process oriented, rather than as summative or authoritative (reinforce learning as dialectic). Generate feedback that includes guidelines on progress made and reminders about assignment parameters and considerations.

4. Use of Collaborative Technologies

[19] Instruct students, as much as possible, on the collaborative technologies being used to support collaborative activities, including their affordances, special features, and complex or poorly designed aspects.

5. Strategies to Support Virtual Teams Start with Trust

[20] Trust is an important aspect of successful collaboration, which can only develop if team members get to know each other. In my technical writing course, team projects come in the second half of the semester, and by then, ideally, students are already familiar with each other through discussion forums and peer responses, if not synchronous meetings. My business communication course requires more intense community-building from the start because all projects except the first one are team projects.

[21] Early-semester activities that promote student interactions not only help students get to know each other, but also demonstrate they have the basic technical proficiencies and the access to technology required to work on a virtual team and produce a virtual team presentation and written report. If some students do not have technology access or proficiency, the instructor who is aware of this early on has a better chance of successfully adapting assignments or providing the instruction needed before the launch of the team project.

[22] For my classes, early activities include asking students to submit at least one question to an FAQ discussion forum about the course syllabus and to produce both written and short video introductions of themselves for their classmates. An important note: Ice-breaker activities welcomed as a social break during a face-to-face class meeting—or even during a synchronous online meeting—may be resented as busywork in an asynchronous online course. In asynchronous courses, activities with a clearly relevant connection to course content and learning outcomes are more likely to be well received.

[23] Instruction in collaborative work helps students to navigate the team project, rather than just learn it as they go. Prior instruction in and ongoing reflection about virtual collaboration is especially important for online team projects because students will inevitably encounter difficulties, even with that grounding. If the course textbook does not provide a chapter on collaboration, recent articles that offer tips for working on virtual teams are usually available online. One that I have found useful is “Making Virtual Teams Work: Ten Basic Principles" (Watkins, 2013).

[24] I developed the following strategies for supporting virtual team projects in my own courses, which also align with my institution’s requirement for writing instructors to provide regular feedback on student work. You may need to adjust these to suit your own course, teaching style, and institutional requirements:

1. Assign teams based on your particular context

[25] How you assign teams in an online course will depend on the particular students in a course section, the project timeframe, and the institutional context. Additional variables could include student engagement in the course and the range of time zones, depending on where the students are when taking the course. Students in the same time zones may have more opportunities for synchronous interaction, and students in the same geographic region may even have opportunities to meet in person. However, asynchronous collaboration is also a good skill to develop and is definitely workable across time zones. Sometimes I organize student teams based on engagement and performance in the course, so that I can provide more support to some teams and allow others to work more independently.

2. Create regular reminders in Canvas Announcements.

[26] Students often need extra reminders about assignments in an online class, especially students who are new to online courses. In Canvas, I can create Announcements with delayed release, which allows me to pre-set a semester’s worth of weekly messages to remind students about upcoming assignments.

Figure 1. Delayed-Release Canvas Announcement

ACCESS TRANSCRIPT OF IMAGE'S TEXT (OPENS GOOGLE SLIDES IN NEW WINDOW)

[27] Since I don’t know exactly what I’ll want to announce each week, I create generic messages titled, “What’s due this week?” and then remind students to visit the Canvas site. This method ensures that a message will go out on a regular basis, even if I forget to add more details. Usually, I continually add to or edit the information in the pre-set Announcement up to the point where it is automatically released. Having regular reminders helps students stay on track and helps maintain my own presence in the course without overloading students with constant emails.

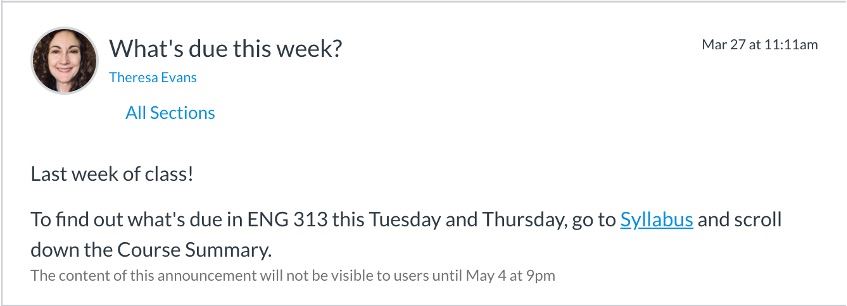

3. Encourage students to start their collaboration by getting to know each other

[28] The social aspect of a project team is important because it helps build trust. To help teams get to know each other, I require several readings, including one on virtual collaboration. In my technical writing course, students are asked to share responses to the readings in small group discussion forums, such as their best and worst experiences with team projects:

Figure 2. Team Trust-Building Discussion Prompt

ACCESS TRANSCRIPT OF IMAGE'S TEXT (OPENS GOOGLE SLIDES IN NEW WINDOW)

[29] In the business communication course project, which is focused on intercultural communication, one of the small group discussions allows students to reflect on a reading about cultural identity, as they discuss aspects of their own identities that they are comfortable sharing.

4. Encourage (or require) students to develop team agreements.

[30] Establishing some ground rules and communication practices for the team is important, and the process doesn’t have to be overly formal. Sometimes I create a simple team agreement assignment through a whole class discussion forum, where one student posts the team’s agreement, and the other team members reply to confirm the agreement—and add their own comments. This allows everyone in the class to see how other teams are negotiating roles and communication practices. Most teams resist assigning rigid roles; however, I do require that they demonstrate specific strategies for communication, since that’s where most virtual collaborations break down.

Praxis Snapshot 1. Team Agreement Prompt

Team Members:

Project Topic:

These are the terms of group conduct and cooperation that we agree on as a team:

Participation: (roles)

Communication: (methods, platforms)

Meetings: (synchronous, asynchronous check-ins)

Conduct: (procedures for peer response and editing)

Conflict: (how to resolve disagreements and misunderstandings)

Deadlines: (internal deadlines to stay on track for project deadlines)

5. Allow students a mix of required and optional platforms for collaboration.

[31] I require students to use a collaborative writing program like Google Docs, but I don’t require access unless the team agrees to provide it or needs to produce evidence to support their contention that certain team members are not collaborating effectively.

[32] I advise students to avoid directly editing the work of teammates and instead use the comment function to offer feedback. This practice demonstrates respect for their peer’s work, and the author can then resolve comments or flag those comments for later discussion in a videoconference meeting. For presentation videos, students can opt to use our institution’s subscription to WeVideo to create an edited video, or they can record themselves presenting “live” in a Zoom meeting. For the most part, I let students decide what platforms to use, and I also demonstrate various options through the videos I create for class instruction. Although an instructor may not have time to try out every possible technology, it is important to understand the constraints and affordances of the platforms student may want to use and to have a realistic idea of how much time producing assignments will take.

[33] Encouraging students to choose a communication platform, such as GroupMe, ensures everyone is “in the loop” and has access to all team communications. Avoid asking to be added to the platforms students choose; provide students the independence they need to truly experience managing a team project on their own.

6. Assign Individual Assignments Related to the Team Project

[34] These smaller assignments are designed to motivate individuals to start developing their contributions to the team project; they are not “busy work.” At the same time, one student’s failure to complete an individual assignment does not affect the grades of teammates.

[35] A good assignment for individual students is a contribution to the team annotated bibliography, which might require each student to provide and annotate the same number of sources. Given that the annotated bibliography is developed early in the writing process, missing this assignment provides an early heads-up about who is not fully engaged. Another individual assignment might be an in-text citation practice: Students are first assigned a video lecture and other resources on the style system the project is using. Next, each student drafts a possible paragraph for the report, integrating and citing a source from the team’s annotated bibliography. By structuring the assignment this way, I can give feedback to individual students on the emerging team draft. I usually do this in a team Google doc that is temporarily shared with me so that team members see my feedback to everyone. Peer response is also assigned as an individual assignment. For example, teams post drafts of their presentation visuals, and individual students provide feedback.

[36] Individual assignments vary, depending on the course. The technical writing course I teach requires a team progress report as one of the major components of the team project. Requiring each team member to write a team progress report provides individuals the opportunity to improve—or reduce—their overall grade on the team project, without affecting other team members. This strategy also helps me to evaluate team dynamics: Not only do I get a more nuanced view of the team’s progress, but I also get an immediately clear picture of who knows what the team is doing and who does not. Students who are most engaged tend to describe the team’s work in specific detail, while those students not fully engaged tend to write in generalities or mistake the progress report as a “feel good” reflection about how well everyone is getting along or the opportunity to “call out” team members. I am transparent about the purpose of the progress report, providing several videos that explain how to write the progress report, why progress reports are important, and what not to do.

7. Assign Team Check-in Points

[37] Team check-in points will also vary depending on the course, and often these assignments are similar to those for face-to-face courses. For example, the technical writing course requires a formal research proposal, so that is an automatic check-in point and an early opportunity for teams to let me know if a team member is not communicating or participating.

[38] For all my online courses, I require one synchronous team videoconference with me to ensure that everyone is “in the same room” at the same time to help address concerns and clear up misunderstandings. No-shows provide information to me about team engagement that I don’t have to seek out, and the points for this team check-in are still awarded to individuals. Instructors should remember to accommodate both accessibility issues and time-zone differences: For example, some students might have to call in on their phone, rather than join by videoconference. When working with students whose locations range from the U.S. Eastern Time zone to China—12 hours apart—one workable option is to set meetings for 9 am EST, so that the students in China are meeting at 9 pm, which is still a reasonable hour. Other team check-in points include the team draft, which allows me to see how far along the teams are in their work and where they need additional support, such as in using in-text citations correctly or organizing their argument effectively.

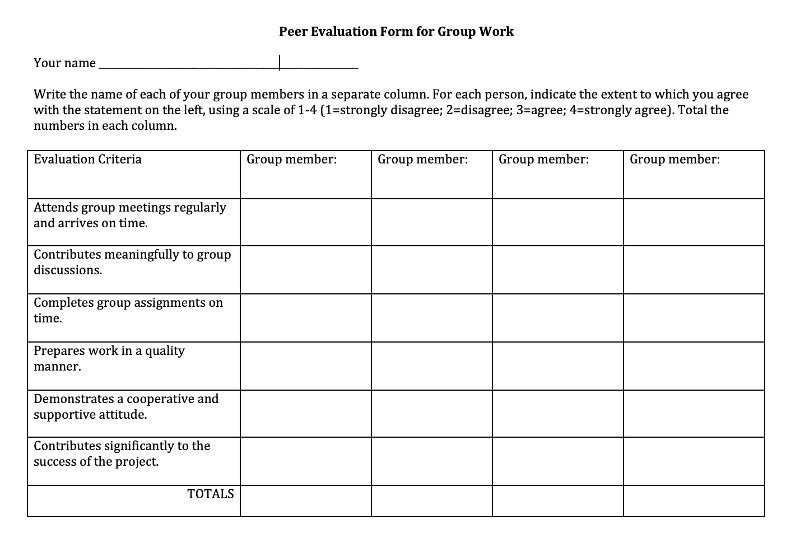

8. Allow Students to Evaluate Themselves and Their Peers

[39] For all my online courses, I use a brief evaluation process where students numerically rank themselves and their teammates on various aspects of the project, and where they also respond to a few questions about their own and their teammates’ collaborative effectiveness. The form I use was adapted by Carnegie Mellon University (n.d.) from a peer evaluation form developed at Johns Hopkins University in 2006. I found the form online, and since then have noted that multiple universities have adapted the form, so it’s easy to find one by using the search terms “peer evaluation form for group work" or "peer evaluation form Johns Hopkins (October, 2006)."

[40] The first page is a quantitative format, where students give numeric scores to their teammates on various aspects of collaboration. The second page offers three questions that prompt them to reflect briefly on team dynamics. In my experience, the scores have reflected team dynamics as much as the answers to the questions. I like this form because it is short, simple, and straightforward. Too many peer-evaluation forms I saw were overly complicated, which I think would result in student frustration and unusable data. Remember, students are probably exhausted from their project. They do want a space to be heard, but they don’t want to write another report.

Figure 4. Peer Evaluation Form Adapted from John Hopkins

ACCESS TRANSCRIPT OF IMAGE'S TEXT (OPENS GOOGLE SLIDES IN NEW WINDOW)

[41] Questions focus on what they learned about team collaboration from the project and which team members were particularly helpful or detrimental to the project—and why.

[42] Students receive a small number of points for completing the evaluation, whether their response is partial or elaborate. I receive additional insights about team dynamics and individual contributions that may confirm what I already suspect or have been told; however, sometimes the responses pleasantly surprise me. For example, some students will acknowledge their own lack of collaborative effort. Others will note that tempering their desire for control and valuing the perspectives and contributions of all team members led to a much better project than they could have completed on their own.

Praxis Snapshot 2. Team Dynamics Feedback Prompt

Feedback on team dynamics:

- How effectively did your group work?

- Were the behaviors of any of your team members particularly valuable or detrimental to the team? Explain.

- What did you learn about working in a group from this project that you will carry into your next group experience?

9. Grade Final Team Projects Individually

[43] Although giving individual grades for team projects may sound like more work, it’s only necessary when there is dysfunction on the team; if a team works well together, then team members should receive the same or similar grades for the team project. One unexpected issue I encountered in Fall 2020 was the extended timeframe my institution allowed students for choosing the pass/no pass option: Team members who chose that option tended to contribute minimally to the team project, which created added stress on students taking the course for a letter grade.

[44] What follows are some options for holding students accountable who have not been fully engaged in the team project:

- If the team had some minor variances in contributions to the project: All team members would receive the same letter grade, but the point values might vary. For example, if the team received a B on the project, then the strongest contributors would receive a high B (87) and those who contributed less would receive a low B (83). This method works best if your grading rubric does not insert specific point values for categories of evaluation.

- If the team had some major variances in contributions to the project: Team members who contributed minimally to the project will have points deducted from the team grade (with an explanation provided). Team members who went above and beyond may have points added to help compensate for an overall lower grade on the project itself.

- If you want to separate the grade for the product from the grade for collaboration: Create a rubric that evaluates the team project and also one category or more to evaluate individual contributions. This option does require more work but can recognize the efforts of students whose team project suffered due to less engaged team members.

[45] Remember, the individual components of the project have already given students the opportunity to do better—or worse—than their team members. Presentation projects (submitted as video) also include the category of oral delivery as an individual grade, which could vary from other team members. Collaborative written reports are more difficult to grade by individual contribution, and I only consider that when a team requests that I review evidence—such as the revision history of their Google Doc—to support their argument that one or more team members have not contributed sufficiently to the project. I don’t consider this surveillance because students have the right to call out team members and to bring team issues to my attention; however, I do ask them to provide the evidence I need to make a decision about project grades.

[46] No matter how well a virtual collaboration project is structured, inevitably some teams will work better than others, and yet “failures” also provide a rich opportunity for student learning.

10. References

Hart-Davidson, Bill (2019). Afterword. Personal, Accessible, Responsive, Strategic: Resources and Strategies for Online Writing Instructors. UP of Colorado.

Carnegie Mellon University (n.d.). Peer evaluation form for group work. Adapted from a peer evaluation form developed at Johns Hopkins University (October, 2006). http://www.cmu.edu/teaching/designteach/design/instructionalstrategies/groupprojects/tools/PeerEvaluations/PeerEval-GroupWork-formsample1.docx

Mehlenbacher, B., Kelly, A. R., Kampe, C., & Autrey, M. K. (2018). Instructional design for online learning environments and the problem of collaboration in the cloud. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 48(2), 199-221.

Paretti, M. C., McNair, L. D., & Holloway-Attaway, L. (2007). Teaching technical communication in an era of distributed work: A case study of collaboration between U.S. and Swedish students. Technical Communication Quarterly, 16(3), 327–352.

Watkins, Michael D. (2013). Making virtual teams work: Ten basic principles. Harvard Business Review, Retrieved June 27, 2013, from https://hbr.org/2013/06/making-virtual-teams-work-ten

Wolfe, Joanna (2010). Team Writing: A Guide to Working in Groups. Bedford/St. Martin’s.