DIY OWL

How to Make Google Suite Work for Online Writing Tutorials

by Chessie Alberti

Publication Details

| OLOR Series: | Research in Online Literacy Education |

| Author(s): | Chessie Alberti |

| Original Publication Date: | 15 September 2019 |

| Permalink: |

<gsole.org/olor/vol2.iss2.d> |

Abstract

This article details the process of designing a method for asynchronous Online Writing Tutoring (OWT) in the institutional context of a community college. By designing an online submission system in Google Suite, we are able to adapt to the changing needs of our students, instructors, and staff. This article examines how Google Suite presents an exciting option for free, bespoke Online Writing Lab administration.

Keywords: OWL, online writing lab, OWT, online writing tutoring, Google Suite, Google Docs, Google Form, online submission, asynchronous, feedback

Resource Overview

Resource Contents

1. Introduction[1] In Fall Term of 2017, Linn-Benton Community College’s Writing Center needed to redesign our system for Online Writing Tutoring (OWT). For the last decade, we had been using a system built, designed, and maintained by Dennis Bennett, the Writing Center Director at Oregon State University (OSU). We called it the Online Writing Lab (OWL), and it operated as the online branch of our Writing Center’s physical location, allowing us to conduct asynchronous sessions with students from a distance [1]. This meant we could reach students who did not come to our Writing Center in person for whatever reason: commute time, work schedule, or simple preference. Students could easily submit their work online, and the administrator received email notifications for new submissions. Once received, each submission could be assigned individually to an appropriate Writing Assistant, who also received a notification in their email. Assistants then had 48 hours to read the OWL submission and write a response, which they copy-pasted into a text box and sent back to the student.

[2] For the last eight or nine years, Bennett had generously hosted our OWL on servers at OSU, but by 2017 it was time for an update. At OSU, they had long since moved their own OWL to a system hosted in Drupal, the university-wide content management system. Bennett offered to continue our partnership with OSU and rebuild our OWL using Drupal but suggested that maybe it was time for us to reach out to our in-house tech people and see what we could do on our own. After all, this might be easier for us to manage without appealing to a third party and meant I would have more control over the administration. It would also give us the chance to incorporate formatting and commenting features that now came standard for most word processors. We were being rightfully weaned, but what next? |

[8] As we began this design work, our priorities laid out as follows:

We started to lean further and further toward an OWL put together using a Team Drive in Google Suite. There were a lot of benefits: students and staff already had Gmail accounts; it would meet privacy expectations; it was easy to use; and Google Docs seemed like the ideal feedback platform. In fact, once I did a little digging in the English Department, it turned out that many students were already using Google Docs for in-class peer reviews. Google Suite is also likely to improve as Google grows as a company, which makes it a reliable choice. |

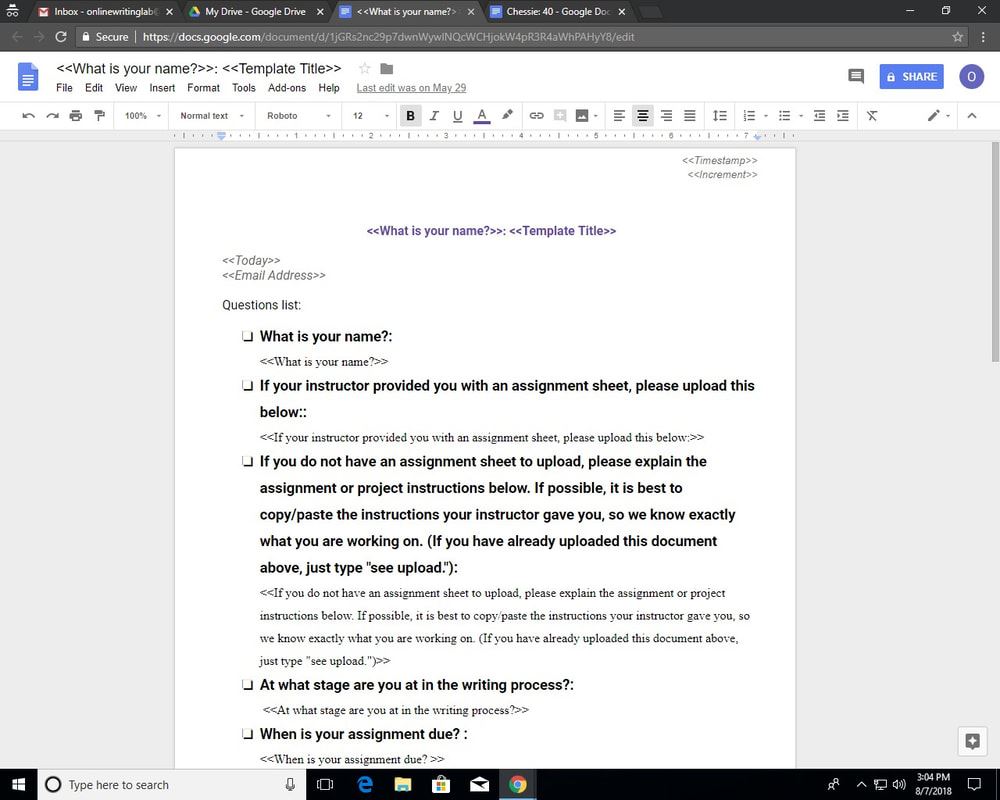

[12] We now had a location to keep our OWL submissions and a way for staff to access them. For staff who had already been trained in the previous OWL, I gave them “edit” permissions. For those who had not yet been trained in the OWL, I gave them “view” permissions. Already, I had discovered one benefit of using Team Drive: for training purposes, it was easy to “step up” the permissions settings as staff became comfortable. Team Drive is also easy to organize, flexible to staff preferences for layout, and easy to use from any computer--or smartphone. It works especially well for off-campus OWL emergencies; for example, it’s easy to double-check that you--or another staff member--completed an OWL assignment after getting home and feeling unsure whether or not the “share” button got hit. [13] This Team Drive also allows us to archive OWL submissions and completed responses. I keep these organized in folders with the submission date and student name, which are then catalogued by respondent name and term. As long as staff are only given “edit” and not “full” access to this Drive, our main OWL account is the only account with permission to move documents or delete files, which keeps organizational chaos to a minimum. Because we have only received 79 submissions during our busiest term so far and individual assistants respond to 16-20 submissions at most per term, it has been manageable to keep our folders tidy. If we had a larger capacity, this archive might be more difficult to navigate, but on our scale it works quite well. 3.3. A Google Form[14] Next, we needed a way for students to submit their work and a way to gather it into the correct spot. I set up a Google Form to capture all of the necessary data. We could customize each question on the Form and include spots to upload documents. We could also restrict the type of files accepted through the OWL, so we could ensure everything we looked at would transfer to Google Docs (they must be .doc or .docx for this to work properly). Even better—and to the delight of our staff--we could require students to answer questions on the form like, “What are your assignment guidelines?” and “What are the strengths of your draft?” before they would be allowed to upload their OWL submission (fig. 3). In the past, we had struggled to build connections with students in an asynchronous context because we did not have the opportunity to require answers to such questions, so including these helps us tailor our responses more effectively to individual students. |

[15] For data collection and archival reasons, I generate a new submission form for each term by simply making a copy of our original form and replacing the URL on our website. This allows us to update the questions on the form if we need to. At the end of each term, I switch the status of our form from “Accepting responses” to “No longer accepting responses.” This closes the form to new submissions and offers a customizable notification should a student still click the link on our website. [16] We also use Google Forms to generate feedback surveys, so we can offer students the opportunity to tell us what they did or did not like about the OWL. A link to a feedback survey goes out with every completed OWL response, and I also send a capstone survey out at the end of each term. This is valuable for ongoing assessment. 3.4. The Form Publisher Add-on[17] The one thing that Google Forms does not do well by itself is generate individual response data automatically in a way that is easy to read and distributable. Instead, it generates as an Excel spreadsheet, which makes paragraph-length responses almost impossible to view. We now had a method for gathering the necessary data and documents, and our next step was figuring out how to extract this information in a visually appealing way and direct it once isolated to the appropriate spot. Google Forms automatically gathers all Form responses into a folder in my Google Drive. So we had a spot for the incoming documents to land, but it is not possible to move entire folders into a Team Drive. Our next step, then, became figuring out a way to direct the appropriate information to the appropriate spot. [18] One of the more valuable features of Google Suite is its embrace of add-ons which are independently developed apps that run inside key Suite features (“Extending G Suite”). If Google Suite doesn’t do it yet, chances are, someone else has built an add-on to make it work. At this point, I had brought all of our Writing Assistants up to speed with my OWL problems, in the hopes that someone might be able to find the missing piece to our workflow puzzle. After some Googling, our Writing Assistant Dani Tellvik discovered an add-on called Form Publisher. Tellvik figured out how to apply Form Publisher to a Form, and we started generating Form Publisher Templates for each incoming OWL submission. As long as the notification settings are correct, each Template will land neatly in a chosen email address. Figure 4 depicts what the add-on looks like within the Google Form, once summoned by clicking the tiny puzzle piece icon at the top of the screen. |

[19] Each template used in Form Publisher is totally customizable, though it is not as intuitive as it could be. Figure 5 depicts what our master template looks like in its third iteration which we have tweaked a few times for content and readability. |

[20] By tweaking code on this master template, you can control what the final template looks like. Figure 6 shows what the template looks like once auto-generated from a Google Forms response. |

[21] As individual Form Publisher templates are generated with each new OWL submission, they land in our main OWL Gmail account. I can then move each template (with all the submission Form answers) into an individual folder in our OWL Team Drive, providing an easy-to-reference guide for each Writing Assistant to consider while composing their response. 3.5. Google Docs[22] Once we receive an OWL submission through the submission form and a Form Publisher template is generated, we move the submitted documents into a folder in our Team Drive and bring the submission itself into Google Docs in order to respond. Because the student has uploaded a copy of their file to the OWL Submission Form rather than simply “shared” it with us, we are the owner of the document and the student will not be notified in real time as we write comments. This allows our Writing Assistants to revise their feedback before sharing it with a student (this could easily be changed by sharing the document with the student before drafting comments, if you prefer synchronous OWT). Writing Assistants then write a greeting up at the top of the document that summarizes the main focus points of their response. From there, they offer contextual comments to highlight examples and provide localized feedback. Sometimes, Writing Assistants also offer an endnote at the bottom of the document to sign off. [23] The length of the feedback letter versus bulk of contextual comments varies by assistant style and personality. We follow pedagogy consistent with CCC’s statement on Online Writing Instruction and the Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors, which call for future-oriented, evidence-based, constructive feedback. Google Docs offers us all the functionality we need to uphold this pedagogy, including features that enhance accessibility for the visually impaired (fig. 7). For a more comprehensive breakdown of what Google Docs has to offer composition pedagogy, see Allison Morrow’s article in ROLE where she makes a compelling argument for the value of working with live documents in Google Docs. |

[24] As Morrow details in her article, an additional feature of Google Docs is that if a student chooses to continue editing on the same document they originally shared with us, we can keep tabs on whether or not they have used our feedback. We also receive notifications as students “resolve” or respond to our contextual comments. If they want to, it is easy for students to ask us follow-up questions or continue a conversation with the assistant who worked on their submission, adding an extra layer of valuable dialogic connection. If students want to, they can also share their OWL response with their instructor or anyone else with an LBCC email address--provided we enable the “link-sharing” option in the document’s privacy settings. |

6. ReferencesExample effective practices for OWI principle 14. (2012). Conference on College Composition & Communication. NCTE. Retrieved from cccc.ncte.org/cccc/resources/positions/owiprinciples/effectivepractices14 Extending G Suite with add ons. (2018). G Suite Developer. Google. Retrieved from https://developers.google.com/gsuite/add-ons/overview Morrow, Allison. (2017). Commenting on student writing: Using Google Docs to enhance revision in the composing process of first year writers. ROLE/OLOR. Retrieved from http://roleolor.weebly.com/limitations.html OWL recommendations? (17 Nov. 2018). WCenter Listserv. Retrieved from http://lyris.ttu.edu/read/messages?id=25257522#25257522 Prince, Sarah; Willard, Rachel; Zamarripa, Ellen, & Sharkey-Smith, Matt. (2018). Peripheral (re)visions: Moving online writing centers from margin to center. WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, 42(5-6), 10. Ryan, Leigh, and Zimmerelli, Lisa. (2016.) The Bedford guide for writing tutors. Sixth ed., Bedford/St. Martin's. What can you do with Team Drives? (2018). G Suite Learning Center, Google. Retrieved from https://gsuite.google.com/learning-center/products/drive/get-started-team-drive/#!/ |