Orchestrated Online Conversation

Designing Asynchronous Discussion Boards for Interactive, Incremental, and Communal Literacy Development in First-Year College Writing

by Dan E. Seward

Publication Details

| OLOR Series: | Research in Online Literacy Education |

| Author(s): | Dan E. Seward |

| Original Publication Date: | 15 August 2018 |

| Permalink: |

<gsole.org/role/vol1.iss1.c> |

Abstract

abstract.

Resource Overview

Contents

| Media, Figures, Tables |

Resource Contents

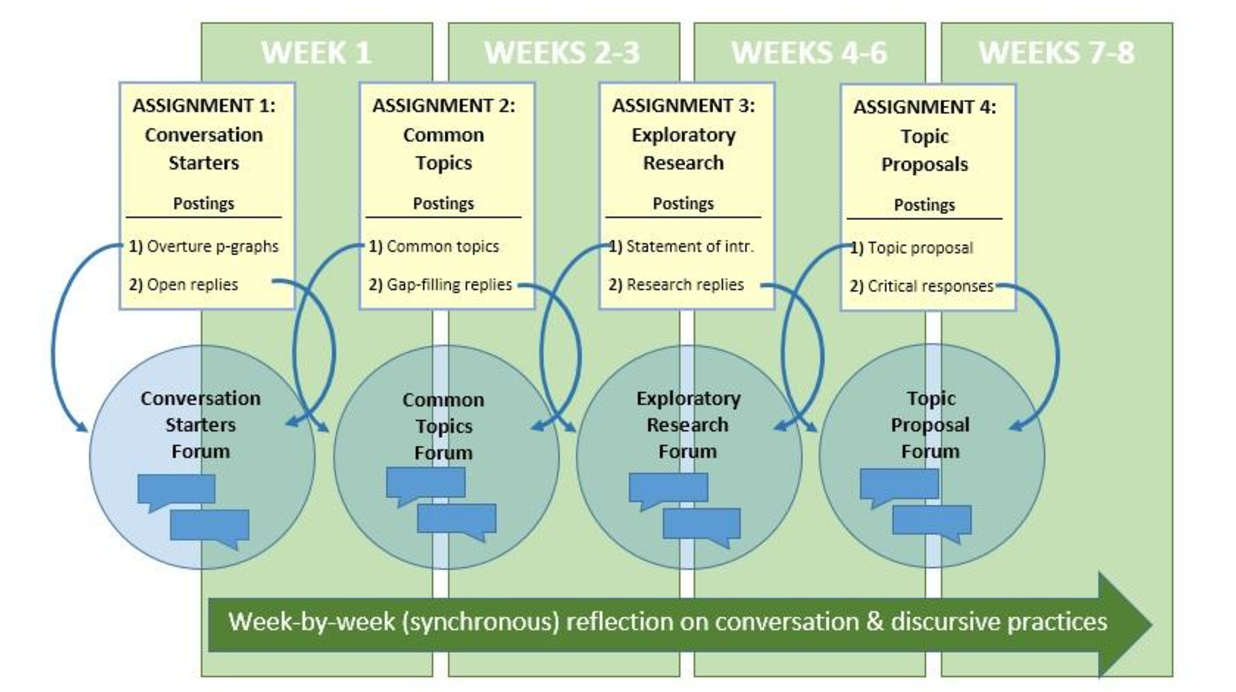

4. Example Implementation: Orchestrated Discussion in First-Year Writing[8] The implementation explained below has been used in the two entry-level writing classes described above. These asynchronous discussion assignments complement each course’s formal paper assignments. As we reach the midpoint of the class, the orchestrated discussion begins to merge with the formal paper writing process, once students start to do exploratory research for their final research paper. This step precedes the submission of a formal topic proposal, which is the focus of the final movement in the orchestrated discussion. The overarching strategy of the discussion design is to transform the initial semi-formal conversation about students’ social, civic, and vocational lives—the broad themes driving these first-year writing courses—into an academic conversation on related subjects, a conversation that students develop with greater analytical depth and critical thinking, as well as by synthesizing their voices with those of outside sources. 4.1. Context of Discussion Assignments within Course[9] As noted above, this strand of course activity occurs alongside other coursework during the first half of class until it finally intertwines with the formal final paper assignment (see Figure 1 immediately below for an overview and Table 1 further below for details). In terms of the course grade, the entire sequence of postings contributes partly to class participation credit (15% of the class grade), but it is also allocated about 20% of the overall course points, a portion that is justified especially by the later postings, which in more traditional classes might be completed offline in conventional forms (e.g., annotated bibliographies) and receive substantial points. But the allocation of substantial points to bulletin board discussions has an important benefit in itself: it validates the online modality—and discussion forums in particular—as a place for serious coursework, especially by integrating an institutional practice (i.e., grading) that, for better or worse, is recognized as a key measure of seriousness for college coursework. Of course, the grading is complemented by other forms of reinforcement, particularly by both peer and instructor validation in replies and responses within the discussion. |

Figure 2. Something

4.2. Pacing of Posting Assignments[10] In the scheme described below, students complete the first postings as they begin the first week of class, an assignment due by midweek for online-only sections and before the first class meeting for one-night-a-week hybrid sections. For both formats, students receive their first assignment before the first week of class to allow them to begin interacting before the first synchronous meeting—there are almost always a few who do. However, when I have used a similar discussion practice while teaching standard-paced sections in traditional face-to-face university settings, I have introduced the first posting assignment on the first day of class, making it due before a later session the same week. In any case, the pacing of the subsequent postings depends upon other class activities. The sequence described below has typically been spread over the first half of the class (3-7 weeks, depending upon the acceleration of the course), leading up to the point where students submit a formal topic proposal for their culminating class research project (as noted above). 4.3. Discussion Board Logistics[11] The postings are conducted on four separate discussion boards (or forums, depending on the platform), and each board corresponding to a movement in the orchestrated discussion. The first threads (or topic posting) in the first movement are initiated by the instructor, but later ones are created by students, reflecting the discussion topics they found interesting the first movement. The posting instructions for both initial thread postings and later response postings are explained in full on assignment sheets, which also have a one-to-one correspondence with the movements in the orchestrated discussion. Where appropriate, the forums themselves contain initial postings created by the instructor, either a directive posting (repeating the prompt explained on the assignment sheet) or a model posting (or both). 4.4. Developing Conversations[12] After the first movement begins, later assignments ask students to review earlier postings and process them in a meaningful way, in some cases, by replying immediately to postings that catch their interests, in other cases, by analyzing their classmates’ postings and developing that analysis into an opening post in a subsequent movement of the orchestrated conversation. We review the work on the discussion boards weekly (usually within web-conferencing sessions or at the live meeting) until students start drafting their final papers after the last movement in the discussion. Throughout, the instructor contributes opening model messages to set a benchmark for the contributions during each round of postings. However, instructors can also reinforce exemplary participation and thoughtful student writing with short affirmation posts. These need not be long: a simple “good observation!” on a message or two can go a long way towards showing the whole class that the instructor does not just view the discussion as “busy work.” The only round of discussion for which I give every student a response is the topic proposal in the final movement of the discussion. [13] The assignment sheets and discussion boards in the diagram above cross the lines for each of the four movements because students typically refer back to the preceding discussion in developing their initial posting for the next and because the first discussion actually starts before the first week’s class meeting. Simply put, the development of each movement of the orchestrated conversation involves a reprocessing of earlier posts, and so students will still be reviewing, maybe even responding to, previous discussion boards as they compose their posts for the next. This directed reviewing and reworking of topics and themes is, of course, the distinctive feature of orchestrated discussion, especially as implemented through counterpoint postings. The table below gives details about the types of postings assigned in each movement of the discussion, and the accompanying video gives full examples of posting prompts illustrating the types of prompts associated with the different genres of postings used in orchestrated conversation. |

5. Technologies and Tools Used[15] The implementation described above and in the videos has been performed on both thread-based and topic-based bulletin-board discussion platforms linked to the class site and individual assignment pages. Regarding the “Reflective Practice” sections, although I tend to present the observations and questions through a synchronous channel (either in a web conference platform, such as Adobe Connect or Elluminate, or, for hybrid, face-to-face), these class reflections can also be conducted through asynchronous means, for instance, via a reflective blog post or on a separate discussion forum designed for course Q & A. However, I try to avoid adding even more text to an already text-heavy instructional modality. A recording of oral commentary is, of course, another asynchronous option. In fact, for the online sections, students who cannot make the meetings are required to view recording of the synchronous session. 6. Acknowledgements[15] As the “Lead Faculty” at a contingent-only, adjunct-driven university, I was charged with developing standardized syllabi for mandated use by all writing instructors. (In other words, at this university, it was not feasible, institutionally speaking, to achieve Principle 5 except within the smallest of scopes.) After integrating the above discussion sequence into the standardized syllabi for the courses noted above, then, I am grateful for the patience, efforts, and constructive feedback provided by the many other instructors who were also required to teach this sequence, which I had adapted from my own previous work as an adjunct instructor at various institutions. 7. ReferencesAmy, L. E. (2006). Rhetorical violence and the problematics of power: A notion of community for the digital age classroom. In J. Alexander & M. Dickson (Eds.), Role play: Distance learning and the teaching of writing (pp. 111-132). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press. Antonette, L. (2006) Critical and multicultural: Pedagogy goes online. In J. Alexander & M. Dickson (Eds.), Role play: Distance learning and the teaching of writing (pp. 133-145). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press. Beckett, G. H., Amaro-Jimenez, C., & Beckett, K. S.. (2010). Students’ use of asynchronous discussions for academic discourse socialization. Distance Education, 33(3), 315-335. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2010.513956 Blanton, L. L. (1998). Discourse, artifacts, and the Ozarks: Understanding academic literacy. In V. Zamel & R. Spack (Eds.), Negotiating academic literacies (pp. 219-235). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. (Reprinted from Journal of Second Language Writing, 3, no. 1, 1994, 1-16.) Bloom, L. Z. (2006). Good enough writing: What is good enough writing, anyway?. In P. Sullivan & H. Tinberg (Eds.), What is “college-level” writing? (pp. 71-91). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English. deNoyelles, A., Zydney J., & Chen, B. (2014). Strategies for creating a community of inquiry through online asynchronous discussions. MERLOT: Journal of Online Learning and Teaching10(1), 153-165. Delpit, L. D. (1998). The politics of teaching literate discourse. In V. Zamel & R. Spack (Eds.), Negotiating Academic Literacies (pp. 207-218). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. (Reprinted from Freedom’s plow: Teaching in the multicultural classroom, pp. 285-296, 1993, by T. Perry & J. Fraser, eds., New York, NY: Routledge.) Elbow, P. (1998). Reflections on academic discourse: How it relates to Freshman and colleagues. In V. Zamel & R. Spack (Eds.), Negotiating academic literacies (pp. 145-170). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. (Reprinted from College English, 53, 1991, 135-155) Freire, P. (1993). Pedagogy of the oppressed (Revised ed., M. Bergman Ramos, Ed. & Trans.). New York: Penguin. (Original work published 1970) Gee, J. P. (2012). Social linguistics and literacies: Ideology in discourses (4th ed.). London: Routledge. (Original work published 1990) Gee, J. P. (1998). What is literacy? In V. Zamel & R. Spack (Eds.), Negotiating academic literacies (pp. 51-60). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. (Reprinted from The Journal of Education, 171, 1989, 18-25) Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. New York: Palgrave. Gillam, K., & Wooden, S. (2013). Re-embodying online composition: Ecologies of writing unreal time and space. Computers and Composition, 30(1), 24-36. doi: 10.1016/j.compcom.2012.11.001 Grafton, A., & Jardine, L. (1986). From humanism to the humanities. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. González, N. (1998). Blurred voices: Who speaks for the subaltern? In V. Zamel & R. Spack (Eds.), Negotiating academic literacies (pp. 317-326). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. (Reprinted from On becoming a language educator, pp. 75-84, by C. P. Casanave & S. R. Schecter, eds., 1997, New York, NY: Routledge.) Hawisher, G., & Pemberton, M. A. (1998). Writing across the curriculum encounters asynchronous learning networks. In D. Reiss, D. Selfe, & A. Young (Eds.), Electronic communication across the curriculum (pp. 17-39). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English. Hendrix, E. H. (2006). A language all its own: Writing in the distance-learning classroom. In J. Alexander & M. Dickson (Eds.), Role play: Distance learning and the teaching of writing (pp. 63-77). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press. Kear, K. (2011). Online and social networking communities: A best practice guide for educators. New York: Routledge-Taylor & Francis. Kittle, P., & Hicks, T. (2009). Transforming the group paper with collaborative online writing. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture 9(3), 525-538. doi: 10.1215/15314200-2009-012 Kutz, E. (1998). Between students’ language and academic discourse: Interlanguage as a middle ground. In V. Zamel & R. Spack (Eds.), Negotiating academic literacies (pp. 37-50). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. (Reprinted from College English, 48, 1986, 387-396.) Lanham, R. A. (1993). The electronic word: Democracy, technology, and the arts. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Lanham, R. A. (1976). The motives of eloquence: Literary rhetoric in the Renaissance. New Haven: Yale University Press. Lewieci-Wilson, Cy., & Cronin Wahlrab, E. (2006). Scripting writing across campuses: Writing standards and student representations. In P. Sullivan & H. Tinberg (Eds.), What is “college-level” writing? (pp. 158-177). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English. Ling, L. H. (2007). Community of inquiry in an online undergraduate information technology course. Journal of Information Technology Education 6, 153-168. Lu, M. (1998). From silence to words: Writing as struggle. In V. Zamel & R. Spack (Eds.), Negotiating Academic Literacies (pp. 71-84). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers. (Reprinted from College English (1987), reprinted in Zamel and Spack, Negotiating Academic Literacies, 71-83. Lunsford, R. F. (2006). From attitude to aptitude: Assuming the stance of a college writer. In P. Sullivan & H. Tinberg (Eds.), What is “college-level” writing? (pp. 178-198). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English. Makri, K., Papanikolaou, K., Tsakiri, A., & Karkanis, S. (2014). Blending the Community of Inquiry framework with Learning by Design: Towards a synthesis for blended learning in teacher training. The Electronic Journal of e-Learning 12(2), 183-194. Retrieved from http://www.ejel.org McCormick, K. (2006). Do you believe in magic? Collaboration and the demystification of research. In P. Sullivan & H. Tinberg (Eds.), What is “college-level” writing? (pp. 199-230). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English. Murphy, E. (2004). Ill-structured problem formulation and resolution in online asynchronous discussions. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology 30(1), n.p. Retrieved from https://www.cjlt.ca/index.php/cjlt/article/view/26532/19714 Olesova, L., Slavin, M., & Lim, J. (2016). Exploring the effect of scripted roles on cognitive presence in asynchronous online discussions. Online Learning 20(4), 34-53. doi: 10.24059/olj.v20i4.1058 Ong, W. (1993). Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Routledge. (Original work published 1982) Ong, W. (1983). Ramus, method, and the decay of dialogue: From the art of discourse to the art of reason. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. (Original work published in 1958) Rendahl, M., & Kastman Breuch, L. (2013). Toward a complexity of online learning: Learners in online first-year writing. Computers and Composition 30, 297-314. doi: 10.1016/j.compcom.2013.10.002 Sands, P. (2006). Distant, present, and hybrid. In J. Alexander & M. Dickson (Eds.), Role play: Distance learning and the teaching of writing (pp. 201-216). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press. Selber, S. A. (2004). Multiliteracies for a digital age. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. Sloane, T. O. (1996). On the contrary: The protocol of traditional rhetoric. Washington D. C.: Catholic University Press. Spiliotopoulos, V., & Carey, S. (2005). Investigating the role of identity in writing using electronic bulletin boards. The Canadian Modern Language Review 62(1), 87-109. doi: 10.1353/cml.2005.0046 Sullivan, P, & Tinberg, H. (Eds.). (2006). What is “college-level” writing? Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English. Warnock, S. (2009). Teaching writing online: How and why. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English. Warnock, S. (2010). The low-stakes, risk-friendly message-board text. In J. Harris, J. D. Miles, & C. Paine (Eds.), Teaching with Student Texts (pp. 96-107). Logan: Utah State University Press. Webb Boyd, P. (2008). Analyzing students’ perceptions of their learning in online and hybrid first-year composition courses. Computers and Composition 25, 224-243. doi: 10.1016/j.compcom.2008.01.002 Yagelski, R. P. (2000). Asynchronous networks for critical reflection: Using CMC in the preparation of secondary writing teachers. In S. Harrington, R. Rickly, & M. Day (Eds.), The online writing classroom (pp. 339-368), Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press. Yancey, K. B. (2003). The pleasures of digital discussions: Lessons, challenges, recommendations, and reflections. In P. Takayoshi & B. Huot (Eds.), Teaching writing with computers (pp. 105-117). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Zamel, V., & Spack, R. (Eds.). (1998). Negotiating academic literacies: Teaching and learning across languages and cultures. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers.

|